Foodist: The Hypocrisy of Free Range Meat

The Atlantic is at it again.

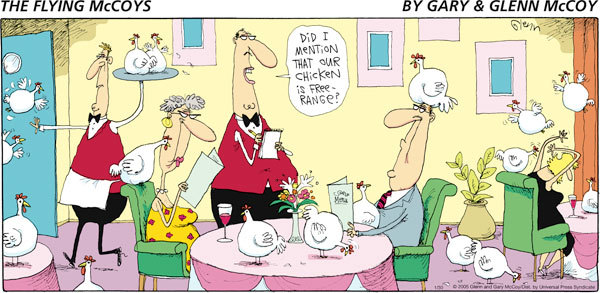

February/March thinking person’s publications, including The Atlantic, Salon.com and even the Chicago Tribune took foodies and locavores to task for, well, “pomposity” and “sermonizing.” It was a tough month for the local food movement crowd. This month in The Atlantic, James McWilliams, an Associate Professor of history at Texas State University, San Marcos, and author of Just Food: Where Locavores Get It Wrong and How We Can Truly Eat Responsibly, talks turkey about the consumption of free range meat. In short, McWilliams argues that animals raised humanely, then slaughtered, are just as dead and consumed as animals raised using less humane methods. Free range meat is not natural.

McWilliams writes:

It’s the strangest thing. Whenever I’m on a panel discussing meat production I seem to be strategically pitted against someone who produces meat through sustainable and more humane (“free range”) methods. What’s so strange is the response I get when I bring up the following conundrum: even if an animal is raised under favorable conditions, we still kill the creature for our benefit and, in so doing, confront a serious ethical dilemma nonetheless.

It’s at this point when the animal farmer addresses me with a condescending expression that says “Yes, James, life can be very harsh,” doing everything but patting me on the head and giving me a lollipop. Then the really odd thing happens: the farmer stakes out a moral high ground on the basis that slaughtering animals is “natural.” The audience smiles knowingly and nods in agreement.

Free range farming is like pornography, McWilliams argues. He suggests that “the appeal to ‘nature’ in free range farming, like most pornography, is essentially disingenuous.”

This precious text comes from the Whole Foods Market web site Meat & Poultry section:

We still do meat and poultry the old-fashioned way, when people cared where their meat came from, how it was raised and how it was processed…We offer organic meats, raised humanely and processed with a measure of compassion, custom cut to your specifications when you want it.

Go to Zingerman’s and have a taste of the $200 per pound ($15 per ounce) free range, acorn-fed Jamón ibérico (cured Spanish pork). If that’s too rich for your blood, you can stop in at Hiller’s for some free range beef, or even Sparrow Market at Kerrytown, where they stock free range poultry.

James McWilliams writes that with free range farmers, and for those buying the products of free range farming, “killing the animal is transformed from an avoidable tragedy into a badge of honor….It’s difficult to imagine any other issue where such a basic sense of right and wrong is so thoroughly perverted. But when it comes to slaughtering animals, even animals raised under the strictest welfare standards, a twisted ethical logic prevails. Killing a sentient being becomes a common good celebrated by food writers and environmentalists in glossy and well-respected publications.”

The University of Michigan Health System recommends free range meat. On the Health System’s food pyramid web site, we read, “We recommend organic, free-range, and grass-fed lean meat products because the animals are raised in more natural conditions and may be more nutritious than meat from conventionally raised animals.”

James McWilliams argues that free range meat is not the least bit natural. Free range farming is contrived. There are fences, automatic feeders, castrations, and of course, slaughter for one purpose: human consumption. In a sense, like fat free water and “organic” maple syrup, free range is just another marketing ploy. Thus, buying free range meat is a distinction to distract us from the guilt. “Natural food” becomes the virtuous, ethically superior choice. This was the same issue Atlantic writer B.R. Myers brought up when he wrote, “The Moral Crusade Against Foodies.” Myers writes:

Even if gourmets’ rejection of factory farms and fast food is largely motivated by their traditional elitism, it has left them, for the first time in the history of their community, feeling more moral, spiritual even, than the man on the street. Food writing reflects the change. Since the late 1990s, the guilty smirkiness that once marked its default style has been losing ever more ground to pomposity and sermonizing. References to cooks as “gods,” to restaurants as “temples,” to biting into “heaven,” etc., used to be meant as jokes, even if the compulsive recourse to religious language always betrayed a certain guilt about the stomach-driven life. Now the equation of eating with worship is often made with a straight face.

Then we have the reality that the free range farming industry is not regulated. Free range regulations require that the animal must be able to move or “roam free.” This does not stipulate what size the area should be. The farmer could be keeping a dozen pigs in an area could be the size of a patio and the meat would still be classified under the regulation of free range meat production.

B.R. Myers goes on to wonder why eating animals slaughtered locally should be a basis for claiming the culinary moral high ground:

But food writing has long specialized in the barefaced inversion of common sense, common language. Restaurant reviews are notorious for touting $100 lunches as great value for money. The doublespeak now comes in more pious tones, especially when foodies feign concern for animals. Crowding around to watch the slaughter of a pig—even getting in its face just before the shot—is described by Bethany Jean Clement (in an article in Best Food Writing 2009) as “solemn” and “respectful” behavior. Pollan writes about going with a friend to watch a goat get killed. “Mike says the experience made him want to honor our goat by wasting as little of it as possible.” It’s teachable fun for the whole foodie family. The full strangeness of this culture sinks in when one reads affectionate accounts (again in Best Food Writing 2009) of children clamoring to kill their own cow—or wanting to see a pig shot, then ripped open with a chain saw: “YEEEEAAAAH!”

James McWilliams, like B.R. Myers, sums up the discussion succinctly when he writes:

The underlying impulse driving farmers to take the moral high ground on the issue of animal slaughter is a vague but powerful sense that the slaughter is justifiable not only because the animal lived a life of freedom under natural conditions, but because the act itself is “natural.” But what if, as I’m arguing here, the free-range experience is nothing but a more humane way to force animals into serving our culinary wants? What if the appeal to “nature” does little more than allow us to forget the reality of enslavement, to take solace in the appeal of false freedom?

In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Tom is allowed to roam the countryside freely, unfettered. In fact, his owner brags about the humane treatment of his “critters,” including Tom, to a slave trader interested in making a purchase. Tom’s is the epitome of false freedom, and as McWilliams writes, it is this false freedom that allows Tom’s owners to forget the reality of the man’s enslavement. Despite his master’s humane treatment of him, and despite his free range upbringing, the inevitable happens and Tom is sold down the river. James McWilliams would tell you that the free range chicken you bought for $18 is no more the result of natural farming, than was Uncle Tom’s humane treatment representative of anything except the cruel reality of his bondage.

@A2GOP you should know by now that nothing is sacred here at A2P except, of course, the profane. @Yale89 I had that same thought when I read McWilliams’s piece! The Atlantic was looking to ignite another firestorm of shares, comments and discussion.

I agree with A2GOP that McWilliams is a provocateur first class. On the heels of the B.R. Myers’ article about foodists it would appear that The Atlantic has found that taking swipes at the ‘natural’ food industry will garner a large audience and a sure reaction.

Since Ann Arbor has a local food movement it makes sense to air views like Mr. McWilliams’ so long as the ‘other side’ gets a chance to respond. So, local foodies, free range meat buyers, farmers, producers, what say you?

I hope you’ll weigh in on the discussion.

First it was the foodies and now free range meat! Is nothing sacred? I suppose not and that’s as it should be. It’s not customary to turn on the bright lights and examine the natural food industry with the same skepticism applied to big agriculture and factory meat production. To me the interesting evolutionary change is that organic produce is now being grown and sold by factory farms that are organic. It is only a matter of time before free range meat is raised and sold by factory meat producers who are free range. This is such a complicated issue and so important to talk about. What’s more basic than food? James McWilliams is out to provoke a reaction I think. Thank you for the thoughtful writing about food. I’m enjoying the A2PFoodist immensely.

@Aubrey, thanks for the insights. Of course animals that produce milk and meat would exist if we didn’t eat them. Cows wander free in India, uneaten in a country where there is serious malnutrition and starvation.

A vegan would say that the only obvious and meaningful change we could make to the lives of animals that are raised for food would be to quit eating them.

Barring that, James McWilliams is of the opinion that free range is not an ethical pinnacle to which we should aspire, but rather just as messy and difficult to justify as any other kind of meat production.

It has been all down hill since we were hunter gatherer’s. The domesticated agricultural diet is killing us it could be argued from all sides, whether organic or conventional. Truly we should be consuming a diverse diet of nuts and berries, and small ground rodents maybe, with lots of water, and physical activity.

In modern conversation free range can mean many things, and it is not always worth the money that that little phrase (not supported by law) touts. I prefer to buy my meat from farmers I know by name, even if they might corn finish. Slaughter methods aren’t going to vary that much between organic and conventional (this is not kosher or halal which are more humane).

Almost all animals being slaughtered in this country are going through the same USDA certified slaughterhouses. You want to know why that Iberico Bellota ham is $200 a pound? Its not because it is free range (that’s how all of the spanish pigs are raised for Jamon), or because of the acorns (which are free because they run the hogs in oak forests). It is because any meat that the U.S. imports has to go through a USDA certified facility (in a foreign country). There is only one Jamon iberico facility exporting at a huge cost to the United States.

From a nutritional stand point, and an energetic standpoint; yes ruminants that consume grass, and live outside are better for you, because that is how they were evolved to live. Ruminants that consume corn and soy and live in enclosed spaces wallowing in their own feces barely able to make it through a year of their life so they are pumped full of antibiotics so they get big enough to make a profit and then they take e.coli 0157 into the food system those are not helping the malnourishment or energy crisis in our country.

Should we eat meat? wheat, potatoes, and milk the way we do? probably not.

Should we pretend like our small choices make no impact on the world?

Free range as we “foodies” tout it, is an idea for how we could all be living our lives, and interacting with our food, and environment and communities. If you aren’t angry about the way that animals live, and only angry that they die, you must not realize that if we weren’t raising these animals for milk and meat they wouldn’t exist at all, and if we can do something meaningful to change the way that animals are raised and die.

@Erik the material comes from The Atlantic. I thought it was a pretty interesting argument, particularly when you take into consideration the lack of regulation of meat that may be sold using the term “free range.” I actually agree with many of your points, personally.

Let me throw this out: I have read over and again that if the U.S. dedicated land that is used in meat production to the production of other kinds of food, hunger could be significantly reduced. Corn is the culprit.

Anyway, thanks for the comment.

The results may be same for the animals, but there are plenty of other benefits to choosing to support sustainable farming practices . To focus on the moral side of things is just part of the story. What about environmental stability and economic diversity (a greater number of smaller farms rather than fewer mega-farms). Mega farms will do everything they can to ensure short term profits (including polluting the land and engaging in unfair / unethical business practices) This is not sustainable.

I think your article could have been have been much more balanced. The main thing it does is encourage the same pompous attitudes on the other side of the issue and discourage personal investigations into truly understanding that what you choose to buy and eat has an impact on our communities and our what shape we are leaving the Earth in for our descendants.

I won’t even go into the nutritional benefits.

Thank you! It’s about time we looked at meat consumption without the rose colored glasses. ‘Natural’ meat is meat! ‘Free range’ meat should not be the moral high ground.

I’m not into dictating what others should eat, do or believe, but I agree with James McWilliams that free range meat is produced using the same basic methods and results in the same end for the animals.