Campaign Finances of Ward 4 Incumbent Show Financial Support Primarily From Ward 4 Residents

by P.D. Lesko

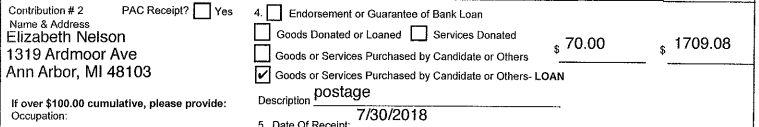

Ann Arbor City Council member Elizabeth Nelson (D-Ward 4) ran as an unknown in 2018 for a four-year term. Nelson is running for re-election in 2022. According to her pre- and post-election campaign finance statements filed with the County Clerk’s office, in 2018 Nelson raised a total of $10,789. In 2018, the bulk of Nelson’s individual donations were small ($100 or less) and came from Ward 4 residents. Nelson’s campaign funding in 2018 included $3,500 in self-funding by Nelson, along with $1,581.37 from her husband Peter Nelson. In addition, Nelson made in-kind donations of goods and services to her campaign worth $1,709. In 2018, over 85 percent of Nelson’s campaign funds were from residents of Ward 4, including herself and her husband.

Nelson’s pre- and post-election campaign finance disclosures for her 2018 race reveal one out-of-state donor ($10 donation) and one out-of-city donation (Michigan Sierra Club Political Committee in Lansing).

Campaign finance records show that Nelson’s challenger Dharma Akmon is primarily funded by big money and donors from outside Ward 4, outside Ann Arbor and outside the State of Michigan. These donors have provided over 70 percent of the Library Trustee’s campaign funds to date.

“The recent focus on fundraising and money as the measure of ‘success’ is highly alarming to me and many others – to whatever extent we accept that as ‘normal,’ our city will never elect anyone who isn’t hooked up to a pipeline of big donors,” said Council member Nelson. “The vast majority of our community is a whole lot of people who either can’t or don’t donate to political campaigns; no one should want a local representative who measures success in donors and dollars,” she added.

In fact, research shows that “small, local contributions to political campaigns have become increasingly relevant. [T]he basic reasoning being that because each donation is so small relative to total campaign donations, small donors cannot be motivated either by an attempt to buy influence nor by any effect they may have on election outcomes.”

Big money donors, conversely, donate for two reasons: to control the outcome of the election and/or to buy influence.

David Mitchell is the Director Of Government And External Relations at the non-partisan voter rights nonprofit Equitable Growth. Mitchell says there are a “myriad ways that economic and racial inequality together subvert our democracy by aiding and abetting political inequality and voter suppression, creating a dangerous feedback loop for the perpetuation of economic policymaking that does not fully represent U.S. communities.”

Dharma Akmon’s campaign finance disclosures paint a clear picture of the influence of racial and income inequality on a political race.

Ann Arbor’s early-August City Council primary election has been sharply criticized by The Michigan Daily as overt voter suppression and gerrymandering, because the majority of U-M students are not present to participate in the selection of their City Council representatives. Pie-shaped wards drawn decades ago split up the student vote.

“Whether intentionally or not, the current ward structure has the effect of basically gerrymandering student votes,” Kenichi Lobbezoo, Ann Arbor Student Advisory Council chair told The Daily in Jan. 2022.

With tens of thousands of student voters effectively disenfranchised, their votes suppressed, Ann Arbor corporate and big money donors are free to try to buy control of City Council. In 2020, the result of big money and corporate funding was the election of candidates who have, repeatedly, engaged in influence peddling.

“We recognize the grossness of this money game at the national level, but unfortunately it has infested our local politics recently,” said Nelson. “I am not a public servant for the purpose of earning people’s donations or impressing the subset of folks who write big checks; I am serving to meet the needs of Ward 4 specifically, and our city overall.”

Ward 4 resident Brandon Dimcheff donated $250 to Dharma Akmon. In response to the A2Indy’s May 2, 2022 article about Akmon’s campaign finances, Dimcheff Tweeted:

Money raised doesn’t, in fact, measure the popularity of a candidate, or guarantee the outcome of an election.

The Ward 4 incumbent said that, “No one should want a local representative who measures success in donors and dollars.”

In 2010, then County Commissioner Jeff Irwin squared off in a run for the Michigan House of Representatives. Irwin’s opponent Ned Staebler took in just a bit more than $100,000 and spent $88,000. Staebler took in more than 60 percent of his money from out-of-district, out-of-state donors. Jeff Irwin raised $47,035 and spent $45,266. The majority of Irwin’s individual contributions came from Ann Arbor residents. Irwin captured 5,051 of the votes cast as opposed to 4,845 for Staebler.

Like Staebler, Akmon’s has raised the majority of her money from donors who can’t vote in Ann Arbor, or in the Ward 4 race. Like Irwin, the majority of Nelson’s campaign funding between 2018-2022 has come from those who can vote in the August primary election.

According to the non-partisan campaign finance research group Opensecrets.org, candidates typically rely on self-funding to provide around 11 percent of their funding and/or big money donors, who provide, on average, 48 percent of a candidate’s funding. Nelson’s self-funding in 2018 was greater than the candidate average. Together with her husband, Elizabeth Nelson self-funded (including in-kind donations) over 60 percent of her campaign expenses.

“I was able to run in 2018 using money I inherited from my dad, but even that (relatively small sum by recent standards) is a barrier to entry. These local offices should be accessible to people like me who simply care about our community and have skills to offer, are willing to put in the work,” said Nelson.

In 2020, U.S. Presidential candidate Michael Bloomberg (D) self-funded 99 percent of his campaign funding: $1.089 billion. On the national level, self-funders almost always lose. In the 2016 cycle, self-funding candidates won only 12.5 percent of the races they ran in, a decline from a 24 percent success rate in the previous presidential cycle of 2012.

Jennifer Steen is a political scientist who wrote a book published by the University of Michigan Press about self-funders in congressional races. Steen says, “A candidate’s chance of winning a primary or general election tends to decrease as the amount of personal funds invested in their campaigns increases.”

While historically, voters have been ambivalent towards mega-wealthy self-funders in national politics, on the local level, for non-incumbents, voters tend to view self-funding differently. Local candidates who are not wealthy and who self-fund are viewed positively, as having skin in the game.

Council member Nelson was asked if she expects to self-fund her 2022 campaign. She said in an email, “I don’t expect to self-fund this year because people know me now and are supporting me. My campaign is also not a contest to see how much money I can raise and spend— I am raising (and continue to raise) what I need for the kind of campaign I believe in at this local level.”

Nelson’s campaign finance reports also show that in 2018 she used Ann Arbor and Michigan businesses to provide her campaign materials, i.e. postcards, buttons, shirts. Akmon’s campaign finance records show the majority of the $2,827 she has spent thus far has been paid to a website designer in Texas.

Nelson’s campaign finance statements submitted after the 2018 general election, include a handful of small ($100 or less) donations from Ward 4 residents. The statements primarily document Nelson’s disclosure of her handling of the loans she made to her campaign in 2018. For example, in a 2021 campaign disclosure statement Nelson declared that she forgave $1,000 of the money she’d loaned herself in 2018.

In 2021, Nelson began to receive donations from residents outside of Ward 4, including $800 from John Floyd, and $300 from Sue Perry, residents of Ward 5, as well as $350 from Peter Eckstein, a Ward 3 resident. Nelson’s campaign finance statements filed in 2021 show a handful of other, mostly small ($100 or less) donations from individuals resident in Wards 1, 2, 3 and 5. Nelson’s most recent (filed in January of 2022) campaign finance statement includes two donations of $100. Both donations came from Ward 4 residents.

Like her opponent’s donors, Nelson’s donors are also predominantly white and non-representative of Ann Arbor’s demographics with respect to race, age and gender.

Laura Friedenbach works for Fair Elections New York. She says, “Such stark underrepresentation distorts who has influence in city hall and diminishes the concerns and needs of a majority of constituents.” Friedenbach added, “A growing body of evidence shows that politicians pay more attention to the policy preferences of the elite donor class, while other concerns facing communities are sidelined.”

When asked why she thinks her donor base has expanded city-wide Nelson said, “My donors are all over the city primarily because the work I have done is unique and has benefited the whole of the community, helping everyone access primary sources and track the work of Council.” Nelson added, “People who care about good government appreciate that I consider issues thoughtfully and I invest a lot of time promoting transparency and accountability. It happens that these values—independence, transparency, and accountability — appeal to many residents outside of Ward 4.”

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.