City Council’s Universal Basic Income Program Could Hurt Low-Income Recipients

by P.D. Lesko

Since Linh Song (D-Ward 2) was elected to Ann Arbor City Council in 2020, the average median household income in the city has risen to $104,000. There are 5,500 people on Ann Arbor’s public housing waitlist for 150 available spots, and the median price of a single-family home has increased to $447,000. Song is a director and treasurer of the Song Foundation, a private foundation (versus a public charity) that controls $24 million in assets. The assets were donated by Doug and Linh Song from the $2.35 billion sale in 2018 of Doug Song’s company Duo Security (Song was one of two co-owners of Duo). Despite her own immense personal wealth, Linh Song championed a City Council resolution to allocate $1.6 million in federal ARPA funds to a two-year universal basic income program for approximately 100 individuals/ families.

According to Council member Song, she grew up in a low-income household where there was food insecurity and domestic violence.

If the recipients are chosen at random from applicants who earn below the $104,000 median household income, the UBI funds could, in theory, go to individuals and families earning $103,000 per year. This rather embarrassing outcome was made possible because Song’s UBI resolution outlined no plan on how to distribute the funds, no guidelines or criteria governing who the target recipients might be, and no concrete goals for how the impact of the funding might be measured. Nonetheless, at its April 4, 2022 meeting, members of Ann Arbor City Council voted to allocate $1.6 million of $24 million in federal ARPA funds to a universal basic income (UBI) program for approximately 100 “low-income” families/individuals.

One issue that was not studied before passage of Song’s UBI resolution was the impact $6,000 in UBI money might have on the recipients’ incomes vis a vis state and federally funded food, health and housing subsidy programs.

For example, in Michigan an individual may qualify for medicaid only with an income of less than $18,075. Michigan’s Healthy Child (MIChild) health insurance program limits participants’ income in a two-person family to $36,620. Michigan’s SNAP foodstamp program places an income limit of $17,667 on individuals and $23,803 for a family of two.

According to officials at Avalon Housing, their low-income renters have income equal to, approximately, $13,000 per year.

For an individual, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the poverty threshold in 2021 was $12,880. This means that, with an income of $13,000, an individual would not be considered below the poverty threshold. For a family of two, the U.S. poverty threshold is $17,420.

A low-income individual collecting Social Security Disability can earn up to $1,650 per month. Add in the proposed $500 monthly UBI to an annual income of $13,000 for an individual, and the individual could see that SSI income reduced. In addition, if that same individual with $13,000 of income was a Michigan medicaid recipient, the addition of $6,000 from the proposed UBI would cause the loss of the medicaid benefit. In Michigan, the income limit for an individual to receive medicaid is $18,075. Likewise, the addition of $6,000 from the proposed UBI to an individual with $13,000 in income who is relying on SNAP food benefits, would cause the loss of those benefits, as well.

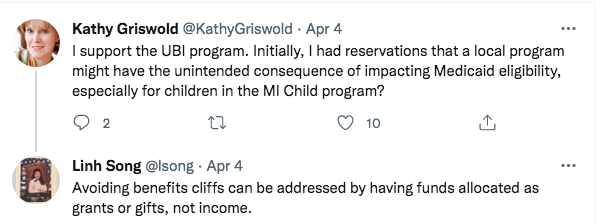

Council member Kathy Griswold (D-Ward 2) was the only one of Ann Arbor’s eleven members who questioned how the UBI might impact the ability of recipients to continue to receive state and federal disability, health insurance and food benefits.

Linh Song Tweeted in response to Griswold’s concerns that UBI recipients could be spared the loss of social security disability, SNAP and medicaid benefits by structuring the UBI as a “grant or gift.” However, neither the State of Michigan nor the U.S. Congress has passed legislation that exempts UBI funds from taxation. As such, UBI recipients in Michigan would be expected to pay both state and federal taxes on their total income, including UBI funds. The Michigan Legislature could change that, of course.

In Sept. 2020, California’s legislature created a universal basic income program of $1,000 monthly payments to residents who elect to receive them. The legislation exempted those funds from state taxation.

Among the 35 UBI programs in the U.S. are:

1. The Compton, CA Compton Pledge program. Compton gives $1,800 every three months for two years to 800 qualified recipients.

2. In Oakland, CA the Resilient Families program gives $500 per month to 600 qualifying recipients for 18 months.

3. In 2021, elected officials in Shreveport, LA began a program that provides single parents, or legal guardians of school-age children stipends of $600 per month for one year.

4. Santa Fe, NM implemented the City of Santa Fe Earn, Learn and Achieve Program. It targets community college students and offers 100 students $400 monthly stipends.

5. In Jackson, MS the Magnolia Mother’s Trust offers 110 low-income, African American mothers stipends of $1,000 per month for one year.

Other cities’ UBI programs focus on formerly incarcerated individuals (Gary, IN and Gainesville, FL), as well as young adults transitioning out of foster care (Santa Clara, CA) and pregnant women (Stockton, CA).

Prior to the statewide program’s implementation, the Stockton, CA Economic Empowerment Demonstration, or SEED, was founded in February 2019 by then-Mayor Michael Tubbs and funded by donors, including the Economic Security Project. It gave 125 people chosen at random living in neighborhoods at or below Stockton’s median household income ($46,033) the unconditional $500 monthly stipend. A study of the period from February 2019 to February 2020, conducted by a team of independent researchers, determined that full-time employment rose among those who received the guaranteed income from the City of Stockton and that recipients’ financial, physical and emotional health improved.

Public engagement related to the UBI program in Ann Arbor included feedback that the UBI program should be limited to Ann Arbor residents, and recipients to individuals and families with incomes at or below Ann Arbor’s $104,000 AMI.

Critics of Song’s UBI program include Jean Henry, former Jefferson Market owner and an Ann Arbor resident. On social media, Henry said in a Tweet that included Linh Song, “I worry about this initiative increasing disparity with neighboring communities. At minimum shouldn’t it be a county initiative or income tested?”

Former County Commissioner Vivienne Armentrout asked Song what would happen to those provided the UBI with the $1.6 million in federal ARPA funding after the funding ran out? Song replied that in other places, the UBI is funded with donations. Unlike Ann Arbor’s UBI program, the Stockton, CA UBI program did not use tax dollars, but was financed by private donations, including a not-for-profit led by the Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes.

Another individual on social media pinged Song: “You can’t pay for childcare or medical debt with $6k.” The Council member replied, “Correct, not all or even most. But even some helps when you need care for medical appointments, interviews, it really doesn’t matter what for…they are examples of what participants have used UBI for beyond basic needs.”

Critics of UBI programs claim that free money discourages recipients from working.

In the research done to measure outcomes of the Stockton, CA UBI program, that study concluded that the UBI funds, “increased recipients’ full-time employment by 12 percentage points.” The study also revealed that, “Individuals spent most of the money on basic needs, including food, merchandise, utilities and auto costs, with less than 1% going toward alcohol and/or tobacco.”

Matt Zwolinski is the director of the Center for Ethics, Economics and Public Policy at the University of San Diego. He told The Associated Press that while the Stockton UBI research findings are “really good news for supporters of a basic income guarantee,” the study is limited because it lasted only two years, adding that people are unlikely to drop out of the labor force if they know the extra money is temporary.

Other UBI opponents include labor unions. There are over 300 million Americans today. Suppose UBI provided everyone with $10,000 a year. That would cost more than $3 trillion a year — and $30 trillion to $40 trillion over ten years. According to the non-partisan Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “this single-year figure equals more than three-fourths of the entire yearly federal budget — and double the entire budget outside Social Security, Medicare, defense, and interest payments. It’s also equal to close to 100 percent of all tax revenue the federal government collects.” In Ann Arbor, a $6,000 UBI for 100,000 residents would cost over $600 million, or nearly $100 million more than the City’s total 2022 annual budget.

Union leaders worry about which other types of social safety net programs would have to be sacrificed to pay for a guaranteed income. A 2019 study conducted for Public Services International, a global trade union federation, found no evidence to suggest that…this approach [UBI] could achieve lasting improvements in wellbeing or equality. The study concluded that, “If cash payments are allowed to take precedence, there’s a serious risk of crowding out efforts to build collaborative, sustainable services and infrastructure – and setting a pattern for future development that promotes commodification rather than emancipation.”

This may help to explain why UBI has attracted support from Silicon Valley tycoons, including Linh and Doug Song. Many of those tycoons are more interested in defending consumer capitalism than in tackling poverty and inequality.

Steve Smith is the communications director for the California Labor Federation. Smith said, “What these [UBI] experiments don’t tell us is what the impact would be as a result of the tradeoffs that are necessary to implement UBI on a massive scale.”

Despite offering up a resolution that included no details about who, precisely, will be targeted to receive the $6,000 in UBI funding, Linh Song says the one-year UBI program will make Ann Arbor “more equitable.” The Public Services International union report concluded just the opposite: “The money needed to pay for an adequate UBI scheme would be better spent on reforming social protection systems, and building more and better-quality public services.”

In other words, collective provision offers more cost-effective, socially just, redistributive and sustainable ways of meeting people’s needs rather than leaving individuals to buy what they can afford in the marketplace.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.