Both Republican and Democratic U.S. Congressional leaders want to see colleges and universities, such Washtenaw Community College, have more skin in the game when it comes to paying for defaulted student loans. Such a policy shift could put WCC on the hook for tens of millions of dollars.

by P.D. Lesko

THE DELINQUENCY RATE on student loans tops that on credit cards, mortgages and auto loans. As a result, U.S. Congressional representatives want to see colleges and universities, such Washtenaw Community College, have more skin in the game when it comes to defaulted student loans. “Risk sharing” — the idea that colleges should bear some of the cost when their students default on federal loans — is the new buzz phrase on Capitol Hill. For WCC, with a student loan default rate of over 20 percent, risk-sharing and proposed fines could cost the community college millions.

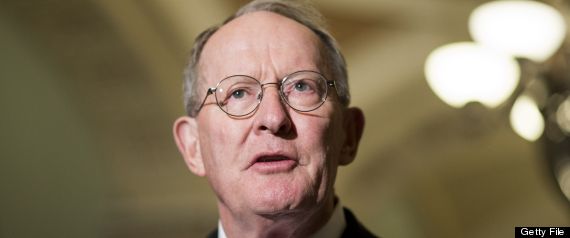

“Using the most recent Department of Education data, more than 1,800 colleges have default rates above 15 percent and nearly one out of every three borrowers defaulted on their federal student loans at more than 200 colleges,” reads a paper released last week by the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions. Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.) chairs the committee and is a leader in the effort to force colleges and universities to take on a portion of the financial burden for the multi-billion dollar problem of defaulted student loans.

As of Feb. 2014, the total outstanding student loan balance was $1.08 trillion, and 11.5 percent of it was 90+ days delinquent or in default. Approximately 7 million borrowers currently hold $99 billion in defaulted federal student loans. According to reporting published in Forbes, “That’s the highest delinquency rate among all forms of debt and the only one that’s been on the rise consistently since 2003.”

Last week, Republican and Democratic senators worked to craft an amendment to the Senate’s spending blueprint for the 2016 fiscal year that expressed support for risk-sharing. The amendment, which would create a “reserve fund” to reform student lending, passed easily.

The size of the average student loan in 2005 was $17,233. By 2012 the average U.S. student loan debt climbed to $27,253–a 58 percent increase in just seven years, according to the financial company FICO.

At WCC, enrollment is down from historic highs and the percentage of students who attain degrees within three years is 15 percent. Thanks to reductions in student aid, student debt is up as are loan defaults.

The student loan default problem may have greater repercussions for the economy than did the housing bubble. According to research from ProgressNow, student borrowers delay major purchasing homes and car, as a result of their student loans. The rate of home ownership is 36 percent less among those currently repaying student debt.

Unlike a car loan, most student loan debt can’t be forgiven in bankruptcy.

This is why regulators and Congressional leaders are starting to pay attention and trying to craft strategies that not only hold students accountable, but hold colleges accountable, as well.

WCC President Dr. Rose Bellanca did not comment when asked about the potential impact risk-sharing could have on her institution’s finances.

There is what is commonly referred to as “the nuclear option.” When colleges’ so-called “cohort default rates” over a three year period as measured by the U.S. Dept. of Education reach 25 percent or higher, students who attend those institutions no longer have access to federally-backed student loan programs. However, Dept. of Education enforcement of the policy has been “uneven and inconsistent,” according to the paper released last week by the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions.

The paper goes on to allege that “some institutions may manipulate cohort default rates by pushing students into deferment and forbearance repayments plans that effectively keep borrowers from defaulting during the three-year window of measurement.” In essence, the paper purports that colleges may be manipulating their own graduates’ loan default rates in order to avoid loss of access to federally-underwritten student loans.

In fact, on the WCC financial aid website, there is a section titled “Deferment and Forbearance.” This link leads to the Federal Student Aid website. There, students are told they may defer for up to three years in the case of unemployment or an inability to find a full-time job.

WCC, then, with a loan default rate of 21.4 percent among its graduates is skirting dangerously close to the 25 percent default threshold at which the federal government imposes the “nuclear option.”

State Rep. Jeff Irwin (D-Ann Arbor) says the risk-sharing proposal “falls in line with a new Republican plan for education. Since they have no real ideas about how to improve education and they certainly don’t want to appropriate the resources to the task, they come up with various measures to push institutions towards a goal that they can laud. We all want graduation rates to go up, so they create a plan to punish institutions that have poor graduation rates. It sounds good at a shallow level, but in the end we punish the very institutions that provide access and opportunity to lower-income students or students who didn’t excel in high school.”

Low Student Completion Rates Contribute

The paper released by Sen. Alexander’s Committee states, “Some institutions have low student completion rates: Just over a half of undergraduate students complete any degree or certificate within 6 years.8 Additionally, many student borrowers who drop out often end up in default. Approximately 70 percent of borrowers who default on their loans withdrew from college before completing their program.”

Washtenaw County taxpayers pay $345 per $100,000 in taxable home value to support Washtenaw Community College. In 2012-2013, county taxpayers paid $45.9 million to WCC officials. In return, the two-year college graduates five percent of enrolled students in two years and 15 percent of students in three years.

County taxpayers give over $3,800 per WCC student enrolled (12,000), but that cost jumps to $25,500 per degree completion (1,800). At Alpena Community College the cost to property tax payers per degree completion (597) is $4,340 and the cost to county property tax payers per student enrolled (1,991) is $1,301.

In order to incentivize colleges such as WCC to lower default rates and boost graduation rates, U.S. legislators have embraced risk-sharing.

Sen. Alexander’s proposal is all at once simple and, for college’s such as WCC, terrifying: “Instead of blunt government regulations and policies that are complex and conflicting, federal law should provide colleges and universities participating in the federal aid programs with market-oriented systems that enable these institutions to lower student borrowing yet still be held accountable for financial risks to students and taxpayers. This new set of policies may be considered risk-sharing or skin-in-the-game.

“Under these proposals, the risk of enrolling a student would be shared among all those who finance a student’s education: the student, the federal government, and now, the institution.”

The idea is that colleges would have a 10-20 percent stake in each loan that originated at the school. At WCC, that would mean a 10-20 percent stake in over $55 million in federally-backed student loans each year for three years after students’ matriculate, transfer or withdraw.

According to WCC’s financial aid website, virtually all of the college’s 12,000 students enrolled qualify for federally-backed student loans and Pell Grants. The annual maximum Pell Grant is $5,500 and federally-backed loan maximums are $12,000, total, for dependent students and $20,000, total, for independent students over the first two years of study.

The risk-sharing proposal suggests setting a college’s risk-sharing percentage equal to the institution’s student default rate. That means WCC could be forced to take a 21.4 percent stake in as much as $55 million in federally-backed student loans annually.

If even 10 percent of the two-year college’s federally-backed student loan pool defaulted, WCC’s liability would be $5.5 million. This would be in addition to “a yearly premium into an insurance fund based on a percentage of the institution’s previous year’s volume of federal financial aid – Pell grants and federal student loans – and other risk factors such as student withdrawals and non-completions,” as proposed by the Senate Committee and supported by both Republicans and Democrats.

Sen. Gary Peters (D-Mich.) said this about risk-sharing: “We need to ensure that higher education is a pathway to economic opportunity, not an overwhelming financial burden for students and families, and I will carefully review any bill regarding student loans that comes to the Senate floor….We need to keep working on commonsense solutions to make college more affordable and ensure students receive a quality education.”