HOLIDAYS: Passover—Picking the Perfect Passover Wine

by Erica Brody

AS THE SEDER draws near, Jews of all stripes become oenophiles, setting out to stores to choose the perfect wine for their Passover meals. As with the meals themselves, which by now include vegetarian and gourmet selections as well as the traditional brisket, kosher wine options have increased exponentially in recent years, leaving brains swimming even before the drinking begins.

The American kosher wine industry came into its own in the late 19th century, when the concord grape was easily cultivated in the Northeast. The grape required a generous addition of sugar to perform that miracle of transforming grape juice to wine, and thus an American Jewish tradition of syrupy sweet wines emerged — with the distinctive taste becoming de rigueur. This was perhaps best summed up in the motto of Schapiro’s wines since the 1890s: “Wine so thick you can cut it with a knife.”

Concord wines — Schapiro’s, of course, along with the ubiquitous Manischewitz and Kedem — for almost a century dominated the kosher market until some American Jews began thinking that perhaps their knives were best kept by their dinner plates. Hagafen Wine Cellars — founded in 1979 — and California’s Baron Herzog — founded in 1985 — offered an alternative and set a precedent for kosher wines to follow.

A recent kosher wine tasting at the Hannah Senesh Day School in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn, a collaborative effort with the neighborhood’s Scotto’s Wine Cellars, offered up roughly 70 wines from around the globe, proving that there’s room in the market for more than Manischewitz. New York’s Gotham Wines boasts more than 250 kosher offerings.

This diversity has met with enthusiasm from Jewish connoisseurs, although some traditions are not to be trifled with. Chef Jeffrey Nathan of the upscale kosher eatery Abigael’s and the author of “Adventures in Jewish Cooking,” told the Forward that he still prefers a concord wine for the Seder’s Four Cups: “It’s the only time I like tradition.” The evening’s meal, however, is an entirely different matter.

Even with the multitude of offerings, the prescribed four cups at one meal is a quantity to reckon with: A cup, in this case, measures between 3.5 and 5 ounces — except, of course, for children and those with extreme health problems. The exact amount has been the center of a rabbinical debate on the interpretation of an ancient measurement — based on the amount of water displaced by an egg, no less, according to Rabbi Moshe Elefant, executive rabbinical coordinator of the kashrut division of the Orthodox Union. While others will opt for grape juice, Rabbi Elefant said that this aspect of Passover is about “showing freedom, pride and happiness, which is better achieved with wine.” A low-alcohol wine like the organic Bartenura Nebbiolo (Italy, mevushal) is good for those trying to keep their wits about them (or hoping to drive home).

“It is considered preferable,” the rabbi added, “to drink red wine.” Why? “In halachic literature red is considered better. It symbolizes a lot of aspects of the night, looks like blood: the blood of the sacrificial lamb, the blood on the doorpost.”

For those with an aversion to red, however, there is a loophole of sorts. Because “Passover is a time for emancipation, it should be done with as much freedom and emancipation as possible,” the rabbi noted. Adding a drop of red wine to either white wine or juice is not uncommon.

Jewish law also dictates that one drink the best wine — meaning either the highest quality or the selection one finds most enjoyable — within one’s means. To that end, the Forward consulted several kosher gourmands — Laura Frankel, chef-owner of Shallots kosher restaurants in New York and Chicago; Avrum Kirschenbaum, co-owner of New York’s Levana; Nathan; Patricia Smith, manager of New York’s Le Marais (which has its Passover label bottled by Baron Herzog), and Anthony Dias Blue, the wine and spirits editor at Bon Appétit magazine — about the wines they’d recommend for the Seder table.

A general rule of thumb emerged among the experts: With gefilte fish, a Chenin Blanc or Chardonnay works well, while the main course is complemented best by a hearty red: Merlot or Cabernet Sauvignon. (Wine aficionados made a point of mentioning that avoiding French kosher wine — made by French Jews — adds insult to injury for a population facing a wave of antisemitism.)

Kirschenbaum added that “years are not important in kosher wine, unless you’re buying a special reserve.”

The small sampling here is meant to illustrate the breadth of wines available for this year’s Passover table, with an eye to tightened purse strings. As Frankel put it, “If you’re going through all the trouble of this ridiculously long meal, you might as well have an extravagant wine to go with it.”

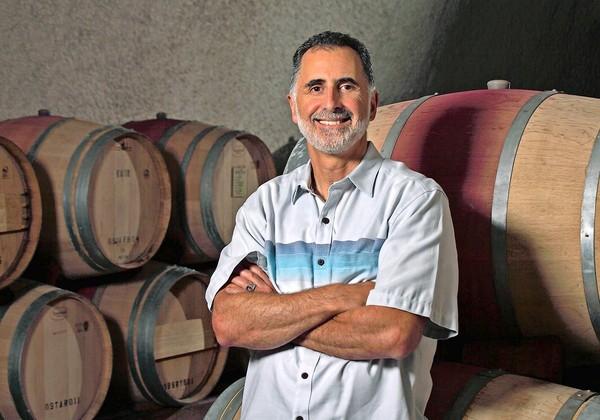

Kosher Wine Suggestions From Jeff Morgan, Vintner At Covenant Wines, Napa Valley

- Domaine du Castel Grand Vin, Judean Hills, Israel 2009

($70)

Castel, one of the top wine producers in Israel, lives up to its reputation with this blend of mostly Cabernet Sauvignon with other Bordeaux varietals. Not surprisingly, this Bordeaux-inspired bottling tastes like really good Bordeaux. The smooth, fine-tuned tannins envelop a core of black currant, blackberry, and herb flavors, and with good length at the end, it’s an excellent choice for dinner.

- Binyamina Reserve Shiraz, Upper Galilee, Israel 2009

($24)

Made in a Rhône style, with just a touch of Viognier, this robust red wine is from one of Israel’s best-known wineries. This blend serves up black cherry, licorice, and black currant flavors and shows a hint of chocolate as well. Smooth-textured, ripe, and ready to drink, it offers terrific value.

- Herzog Special Reserve Cabernet Sauvignon, Napa Valley 2007

($38)

From California’s benchmark kosher winery, this wine is sourced from vineyards in the Napa Valley. 2007 has been hailed as one of the best vintages in the last decade, and this wine shows the year’s pedigree. With its complex layers of plum, currant, vanilla, and spice—all framed in toasty oak—this wine offers great value for a Cabernet from the region.

- Capçanes Peraj Ha’abib Flor de Primavera, Montsant, Spain 2009

($60)

An intriguing blend of Grenache, Carignan, and Cabernet Sauvignon, this is the premier kosher wine from Spain. It’s worth exploring with its bold raspberry, black cherry, and spice notes, all set against firm, ripe tannins and toasty oak.

- Covenant Chardonnay “Lavan,” Russian River Valley 2010

($38)

Lavan (which means “white” in Hebrew) is a full-bodied white wine that serves up a fine-tuned blend of mineral, stone fruit, toast, vanilla, and citrus flavors. Barrel-fermented for lush texture and complexity, it’s got bright acidity and can stand up to all sorts of rich dishes. But it also has enough elegance to pair well with lighter seafood and soups. The wine is unfiltered to best highlight flavor.

The Finer Points Of Kosher Wine

What’s the difference between kosher wine and kosher for Passover wine?

In order for a wine to be kosher, it must be created under a rabbi’s immediate supervision, with only Sabbath-observant Jewish males touching the grapes from the crushing phase through the bottling.

While all wines require some sort of mold (yeast) for fermentation, kosher for Passover wine must be made from a mold that has not been grown on bread — sugar or fruit are often used to create yeast —and must exclude several common preservatives, like potassium sorbate. Most kosher wines are kosher for Passover, but not all, so it’s best to check the label.

What’s mevushal?

Once a bottle of non-mevushal kosher wine has been opened, it must only be handled by Jews if it is to remain kosher. At family Seders where non-Jewish guests or hired help will be pouring or passing wine and in kosher restaurants, mevushal wines are used. Mevushal wine is a wine that has been brought to high temperatures, which allows it to maintain its kosher standing no matter who pours from the bottle. The traditional method of creating mevushal wine — boiling — has been replaced, thanks to new technologies, with a flash pasteurization process that in just seconds brings a wine to the necessary temperature (between 170 and 192 degrees). This allows a mevushal wine to stay both tasty and kosher, helping Seder goers to celebrate their freedom with friends and family who aren’t Jewish.