ARTS & LEISURE: Looking To Make The World A Better Place? Read Crime Fiction

by Ken Wishnia

Sometimes the only place where bankers go to jail for their criminal activities is in the pages of crime fiction.

LET’S FACE IT: some of the most ideologically committed people rarely read fiction, even socially conscious fiction, which means they’re only getting part of the story.

If you’re writing a research paper on the Great Depression, you’re probably going to start off by reading non-fiction accounts of the events of that decade. But if you want to know what it actually felt like to lose your home to the banks, travel across the country just to work a seasonal job with long hours under appalling conditions, and get assaulted by vigilantes because you dared to speak up, you should look no further than John Steinbeck’s masterpiece The Grapes of Wrath.

The same goes for crime fiction.

Crime fiction has the longest tradition of progressive social criticism of any American popular literary genre.

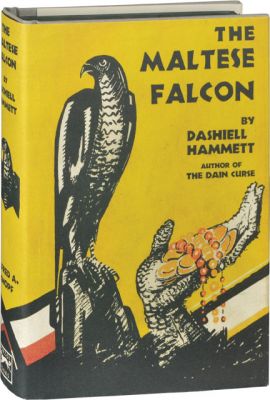

While some of today’s best-selling authors are attracted to the vigilante law-and-order and CIA-assassin type of crime thrillers, American hardboiled crime fiction began as a product of the rampant lawlessness and corruption of Prohibition in the 1920s. Dashiell Hammett, best known for The Maltese Falcon (1930), worked as a Pinkerton detective for several years and witnessed the violent suppression of the Anaconda copper miners’ strike in 1920. His first novel, Red Harvest (1929), draws on that experience, set in a mid-sized western city that is completely controlled by two rival criminal gangs. (One of my favorite lines from this novel: “The room was as dark as an honest politician’s prospects.”)

While some of today’s best-selling authors are attracted to the vigilante law-and-order and CIA-assassin type of crime thrillers, American hardboiled crime fiction began as a product of the rampant lawlessness and corruption of Prohibition in the 1920s. Dashiell Hammett, best known for The Maltese Falcon (1930), worked as a Pinkerton detective for several years and witnessed the violent suppression of the Anaconda copper miners’ strike in 1920. His first novel, Red Harvest (1929), draws on that experience, set in a mid-sized western city that is completely controlled by two rival criminal gangs. (One of my favorite lines from this novel: “The room was as dark as an honest politician’s prospects.”)

Raymond Chandler, best known for The Big Sleep (1939) and Farewell, My Lovely (1940), perfected a cynical style in response to the ravages of the Great Depression, the systemic corruption, brutality, and racist tendencies of the LAPD, and the age-old unwritten rule of “one law for the rich, another law for the rest of us.” Chandler’s polished writing style can turn a drive from downtown Los Angeles to the Hollywood hills into a sociological essay on the class dynamics of each neighborhood that his detective Philip Marlowe passes through.

Closer to our own era, authors such as Marcia Muller, Sara Paretsky and K.C. Constantine have staked their claims to this territory, and opened up a path for a host of worthy descendents.

Crime fiction exposes the social conditions that lead to crime.

Walter Mosley’s first novel, Devil in a Blue Dress, was made into a film in 1995. I once heard him tell an audience, “Hollywood wants a Ku Klux Klansman and a Black Panther to watch the same movie,” because the filmmakers had cut most of the racial politics depicted in his novel so as not to risk alienating potential ticket buyers. This is one reason why in so many films and TV shows featuring serial killers, the typical story line is about catching the killer before he kills again, but there is no indictment of the larger society that produced him.

It’s not as simple as the cliché that “society made him do it.” But there is clearly something about U.S. society that makes us number one in serial killers in the world. We also have the most gun deaths of any stable, industrialized democracy, and the fact that apocalyptically-inclined extremists and other mentally unstable people have such easy access to guns is a major factor. But the country’s violent history — of genocide against the Native American population, enslavement of African-Americans, and imperialist expansion beyond our borders — is surely a factor as well.

The effects of this violent history play out on many levels. If you want to experience a powerful depiction of how Americans’ devotion to the culture of football produces and condones brutal group behaviors and allows star athletes to get away with rape and other crimes, read S.J. Rozan’s novel, Winter and Night.

For progressive writers, depicting violence is not about sensationalizing the gore or titillating with torture porn, it’s about describing the violent consequences of racial prejudice and economic inequality, and the long-term effects of such violence, which may last for decades. Check out Gary Phillips’s Ivan Monk novels or Reed Farrel Coleman’s Moe Prager novels and you’ll see what I mean. And if you want to immerse yourself in the poverty and depravity in the Missouri Ozarks, read anything by Daniel Woodrell, author of Winter’s Bone.

We also write about white-collar crime, or as we call it, greed.

Not all sociopaths are violent killers. Some of them even rise to the rank of Vice President of the United States (I’m looking at you, Dick Cheney). After all, sociopathic behavior is rewarded on Wall Street, and Paul Ryan’s Ayn Rand-inspired budget proposals were clearly produced by people with an astonishing lack of empathy for anyone who doesn’t belong to their exclusive circle of wealthy and well-connected donors. (Hammett and Chandler would have been right at home writing about this crowd.)

And the most successful of them get others to do the actual killing.

The problem with so many financial crimes is that they’re just not considered “sexy” by the media. Everyone gets that Bill Clinton was impeached because he dropped his pants in the Oval Office and tried to lie about it afterwards. But try to explain the Savings and Loan Crisis of the early 1990s, or the BCCI scandal, or the Enron meltdown, or more recently, how predatory lenders ruined the lives of millions of homeowners, and people’s eyes glaze over.

The 19th century French author Honoré de Balzac once wrote, “Behind every great fortune lies a great crime.” It is the writer’s job to expose the great crimes behind the great fortunes, and sometimes, the only place where bankers go to jail for their criminal activities is in the pages of crime fiction.

Fight back against the dumbing down of our culture.

Admittedly, a lot of contemporary crime fiction is mindless escapism. But the best crime writers use their fiction as a vehicle for drawing attention to the suffering of the little guy. There’s a quote often attributed to Josef Stalin: “One death is a tragedy, one million deaths is a statistic.” It’s our goal as writers to dramatize that one, tragic death and make the reader feel the pain, sorrow, loss, and injustice of it.

So, while everyone else was spending their time reading celebrity gossip, watching “entertainment news,” and debating the implications of Miley Cyrus twerking on national TV, crime writers were exploring the dark underbelly of American culture and denouncing the suffering we found there, in the shadows.

You’ll be supporting progressive writers.

The system as it currently exists is set up to reward the authors of popular fiction that does nothing to challenge the status quo. But you have the power to change the dynamic, because if you read more progressive crime fiction, the publishers just might take notice.

So take some progressive crime fiction to your next demonstration, Occupy Wall Street-type action, or sit-down strike. It’ll help pass the time between speeches, believe me.