Of State’s College Students Who Took Tough New Teacher Certification Tests, U of M Students Did Best and Worst

At one U of M campus 63 percent of students seeking teaching certification passed the examinations. At another U of M campus, only 8 percent of students tested passed.

by Ron French

Bridge Magazine—Teacher prep programs at Michigan colleges and universities are scrambling to adjust to the state’s beefed-up teacher readiness exam, first given this past fall, that rated only a quarter of aspiring teachers ready for the classroom.

The panic is being felt from the halls of Michigan State University’s nationally renowned school of education, where less than a third of students passed the test, to Ferris State University, where no aspiring teachers passed.

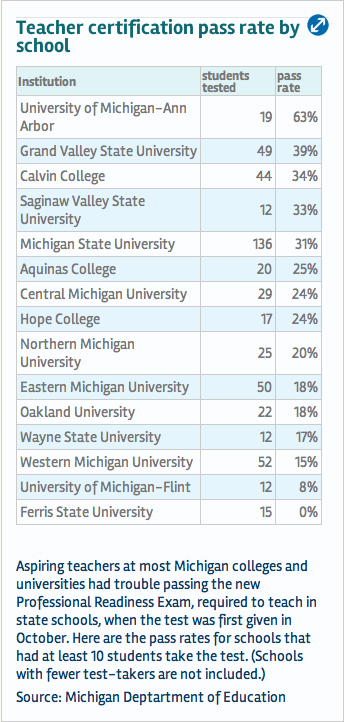

At the request of Bridge Magazine, the Michigan Department of Education recently released student pass rates for each of the college-level teaching programs in the state. The results were humbling. The University of Michigan had the highest pass rate at 63 percent. But at nine of the 15 schools at which at least 10 students took the exam, less than a quarter of students passed.

Those who may eventually benefit the most from the tougher exam will never see the test – Michigan’s children. The new certification test, which all new teachers must pass to teach in Michigan public schools, is part of an effort to assure that only the most highly-qualified teachers are leading Michigan classrooms.

“These results presented a wake-up call not just to students who did not pass the test,” writes Donald Heller, dean of MSU’s College of Education, in a Bridge guest column, “but to schools and colleges of education across the state.”

That was the goal, according to State Superintendent Mike Flanagan. “Just like we’d want the best and most effective doctor, the same applies to teaching Michigan’s students,” Flanagan said in November about the new, low pass rates.

Michigan teacher prep lacking

Beginning last September, Bridge Magazine published a series examining the crucial role of teacher preparation in increasing learning in Michigan classrooms, where test scores show students are falling behind others in most states.

Aspiring teachers at most Michigan colleges and universities had trouble passing the new Professional Readiness Exam, required to teach in state schools, when the test was first given in October. At the time, aspiring Michigan teachers had a similar pass rate on certification tests to cosmetologists, raising questions about how seriously the state considered the issue of getting only the best prospective teachers into classrooms.

The new test, first given in October, was designed by K-12 and college educators to raise the bar for entry to the classroom. Whereas the old test merely required aspiring teachers to show the knowledge needed for “an entry-level teacher,” the new test demands students demonstrate they have the knowledge to “effectively perform” as a teacher.

The result is a much more rigorous exam, with higher-level math questions and a tougher writing subtest. The previous statewide pass rate of 82 percent dropped to 26 percent on the new test.

Students can retake the test – which is offered four times a year – as many times as they like, so students who failed in October still may eventually become teachers. But some students who struggled with the exam may decide to pursue another field of study. This is especially true at colleges that use the exam as a de facto admission test to the teacher training program, said C. Robert Maxfield, interim dean of the School of Education and Human Services at Oakland University.

The exam, called the Professional Readiness Exam, is just the first step to getting a teaching license in Michigan. Beyond passing the PRE, students must successfully complete student teaching, as well as area-specific exams (elementary education, secondary social studies, etc.).

The state also requires that aspiring teachers pass the PRE before beginning student teaching, typically as seniors, but about half of Michigan college prep programs require students to pass it before entering their program, typically as sophomores.

The state also requires that aspiring teachers pass the PRE before beginning student teaching, typically as seniors, but about half of Michigan college prep programs require students to pass it before entering their program, typically as sophomores.

At Oakland University, where students must pass the test to enter the teacher prep program, only 18 percent passed last October.

“If something doesn’t happen quickly,” Maxfield said, “we’re not going to have anyone in our program.”

The Department of Education cautions that the pass rates may change as more students take the test. Schools aren’t waiting, though, to adapt to the new test.

Oakland University is offering tutoring to students who are preparing to take the exam.

“That’s a quick fix,” Maxfield said. “But (in the long term) it needs to be addressed in the curriculum of general-studies classes,” the math and English courses students take in their first two years at Oakland.

Ferris State’s School of Education is reexamining its policy of mandating students pass the PRE before entering the teacher program as sophomores or juniors with the belief that, with another year of school under their belt, more students would pass. The state only requires that the PRE be passed before a student begins student teaching. About half of the state’s teacher prep programs require a passing score to enter programs, and half after entering the program but before student teaching.

“I understand the state’s position. We really want to know whether they are ready to teach,” said James Powell, director of the School of Education at Ferris State. “The question is, how much debt do we want them to take on before knowing whether they can student teach?”

Powell said Ferris faculty is working on test strategies with students who want to be teachers, as well as examining whether core curriculum needs to be strengthened.

Some questions about exam

Some schools are raising questions about the limits of what the testing reveals. MSU’s Heller wrote in a College of Education blog that the school’s pass rate dropped precipitously even though the MSU students taking the exam had high ACT scores and college GPAs.

The state “likely knew the cut scores (the minimum score to pass) they chose would result in a much lower passage rate than in prior administrations of the test,” Heller wrote. “But whether the specific cut scores actually will ensure that these students will be the future ‘best and brightest’ teachers is unknown. The process may just end up selecting the students who are the best test takers, but not necessarily those who will be the best teachers.”

Flanagan addressed the issue of more stringent cut scores at the November meeting of the state Board of Education. “If we wanted to temper (cut scores to allow more students to pass), it would have been overruling actual practitioners who said this is what you need to know to pass the test.”

Ming Lee, dean of the College of Education and Human Development at Western Michigan University, called the test results “disappointing,” and suggests the state may need to find a way to identify and screen for characteristics of good teachers in addition to test scores.

Deborah Lowenberg Ball, dean of the University of Michigan School of Education, said it is “absolutely important to require teachers to know subject matter content. It is also crucial that the questions on the subject matter exams test the content that teachers have to know well in order to teach, and that the test items assess that kind of knowing of content that is most important to skillful teaching.”

The state is also slowly revamping its teacher certification tests in specific subjects to make them as rigorous as the PRE, with the hope that a higher bar for entrance to the teaching profession will eventually lead to better teaching and higher academic achievement among Michigan students.

“This steps up our game,” said Maxfield, of Oakland University. “We just have to do an increasingly good job or attracting the brightest and most capable students to teaching.”