Since 2005 U of M Financial Aid Spending Up 1.8 Percent While Tuition & Fees Revenue Up 50 Percent

STATE APPROPRIATIONS TO the University of Michigan dropped from $320,662,000 in 2005 to a projected $279,108,700 in 2014, a loss of a total of 12.9 percent over the past descade—some $41.5 million dollars. Drops in state appropriations to the University have been repeatedly cited by Dr. Mary Sue Coleman as the primary reason for increases in tuition. In February 2013, Dr. Coleman appeared before the Michigan House Appropriations Subcommittee on Higher Education and told the group: “We know we have to have tuition increases, particularly because the state has not been able to invest in us the way we would like. I am very cognizant of the burdens on families, but I am also cognizant of my responsibility to keep this place competitive.”

Between 2005 and 2014, the University of Michigan’s income from tuition and fees rose from $675,392,000 to $1,156,646,746, an increase of $481,254,746—over 10 times the total amount lost from state appropriations over the same period.

The 2013-2014 University of Michigan budget contains another surprise. While students, their parents, federal subsidy and loan programs paid to meet substantially higher costs for tuition and fees assessed by the University of Michigan between 2005 and 2013, officials at the University of Michigan increased the amount allotted to centrally awarded financial aid just 1.8 percent in ten years. Pay for upper-level administrators, during that same period, increased by as much as 150 percent.

The Office of the Provost prepares a budget presentation for the Board of Regents each year. That presentation includes “highlights.” In the fiscal year 2014 General Fund Operating Budget Recommendation, Provost and Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs Martha E. Pollack writes, “The budget proposal includes the lowest in-state undergraduate tuition rate increase in nearly 30 years, demonstrating our commitment to the families and students of the state of Michigan….The budget recommendation includes our largest dollar investment ever in undergraduate financial aid along with the lowest tuition rate increase for in-state undergraduate students in nearly 30 years.”

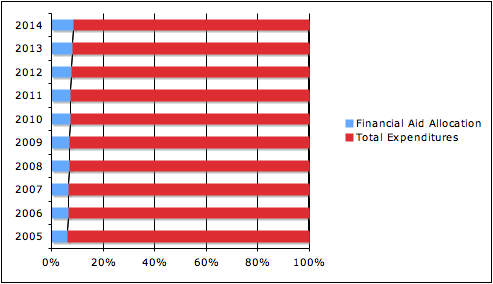

However, as a percentage of total expenditures, the amount allocated to centrally awarded financial aid has increased just 1.8 percent over the past decade.

Provost Pollack’s statement that “The budget recommendation includes our largest dollar investment ever in undergraduate financial aid” is accurate. In 2005, the University of Michigan’s General Fund allocated $78,099,000 to centrally awarded financial aid and in 2013 officials allocated $144,768,261, a substantial dollar amount increase.

However, during the same nine year time period, total expenditures increased, as well. In 2005, the University of Michigan’s General Fund budgeted a total of $1,163,382,000 on funding for the college’s schools (academics), administration (executive officer and service units), as well as financial aid.

In 2013, the University of Michigan’s General Fund budgeted a total of $1,649,139,526 on funding for the college’s schools (academics), administration (executive officer and service units), as well as financial aid.

The $144,768,261 allocated to financial aid in 2013 represents 8.5 percent of the total expenditures while the $78,099,000 allocated to financial aid in 2005 represented 6.7 percent of the total expenditures.

The University of Michigan’s 2014 General Fund budget projects a $61.1 million dollar increase in revenues from tuition and fees, as well as a $16.4 million dollar increase in the dollar amount allocated to centrally awarded financial aid. Should the budget projections prove accurate, this will mean that the amount of General Fund money allocated to financial aid as a percentage of overall General Fund spending will be 9.3 percent or a total 2.6 percent increase since 2005.

This means that between 2005 and 2014 the amount the University of Michigan collects from students, parents, federal tuition subsidies and loans will have increased by some $560,758,087, or about 50 percent. Viewed in comparison to a 2.6 percent increase in General Fund money allocated to financial aid, students, parents and federal sources are left filling a large gap. It’s a gap that has created a tsunami of blow back as undergraduate and graduate students protest their own rising indebtedness and politicians jump on the Student Debt bandwagon.

According to research by the Pew Trusts and published in 2006, “Statewide average debt for seniors graduating from public universities ranged from $23,198 in Iowa to $11,067 in Utah.” In 2005, a Michigan college student’s average debt load at graduation was $18,942 or the 18th highest rate in the nation.

Again, according to research by the Pew Trusts, by 2012 in the U.S., “Seven in 10 college seniors (71%) who graduated had student loan debt, with an average of $29,400 per borrower.” Three-quarters of Michigan college students graduated with some debt. The average debt of 2012 graduates in the state was $31,520 making Michigan’s ranking the 10th highest in the nation.

According to a 2012 report by online Bridge Magazine, “About one in 10 student loans wind up in default in Michigan, about average for the country. But more of those defaults are taken to federal court because the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Detroit has been aggressive in pursuing judgments.”

Bridge Magazine also reported, “Analysis found that Michigan college students leave campus with higher debt than the national average, a reflection of higher average net costs at public universities.”

While the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor has one of the lowest student loan default rates in the state, at 2.9 percent in 2010, in 2009 the rate was 1.6 percent, meaning that the total number of Ann Arbor graduates in default almost doubled in a single year. In 2010 7.7 percent of U of M-Dearborn students defaulted on their loans and 12 percent of U of M-Flint students defaulted on their loans, a default rate just slightly lower than that of Wayne State University graduates, 12.5 percent of whom were in default on their student loans in 2010, one of the highest 4-year student loan default rates in Michigan.

At both Harvard College and at the University of Michigan, 70 percent of all students receive some form of financial aid. However, a look at the income cut-off levels used to calculate the amount of aid given to the lowest income families reveals that University of Michigan requires the largest contributions from the families who have the least to give.

Harvard Magazine recently reported that Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) spent $212,000,000 on financial aid out of tuition revenues that totalled $419,000,000 in 2011. Students whose family incomes are $65,000 or less pay nothing at Harvard, but are expected to participate in work study programs. Families with earnings of between $65,000 and $150,000 are expected to contribute from 0-10 percent of their incomes.

At the University of Michigan, a family with an income of less than $20,000 can expect to pay 12 percent of that income to cover the cost of books and supplies. This need is expected to be met through federal work study programs.

Families with incomes of between $20,001-$40,000 can expect to pay $6,098 per year for a child to attend Michigan, or between 15-30 percent of their income to cover 25 percent of the cost of housing, as well as the cost of books and supplies. Families with incomes as low as $20,001 are expected to take out annual $2,500 loans and pay $500 toward costs.

Families with incomes of $40,001-$60,000 can expect to contribute $8,308 per year, including $2,500 in federal loans, and a $3,218 family contribution, costs that amount to 14-21 percent of those annual family incomes.

Unlike at Harvard, where families with incomes above $150,000 are expected to pay a higher percentage of their incomes than lower income families, University of Michigan’s Financial Aid policies require lower income families to contribute a proportionally higher percentage of their annual incomes.

A family with an income of just $20,001 with a child who attended U of M for four years, would be expected to make a $10,000 loan contribution (not including interest), plus $2,500 in cash, a burden equal to 15 percent of that family’s income.

Dr. Coleman has repeatedly stressed the need to keep Michigan “competitive” and cost-cutting efforts to reduce fixed cost expenditures.

Financial aid data suggest the fast-paced growth of expenses at Michigan has little, if anything, to do with the amount of centrally awarded financial aid given to students. On the contrary, students and their families—particularly families with the lowest incomes—are increasingly expected to shoulder the growing costs through tuition and fee assessments that have seen the cost of tuition rise 200 percent since 1990.

Data suggest that state appropriations, up since 2012, have been used as a pretense to increase tuition and fees. Next week, The Ann Arbor Independent will look at U of M’s efforts to rein in costs. This effort has been one of Dr. Coleman’s consistent talking points as she has asked politicians to boost state appropriations.