THE 2013 NON-MOTORIZED Transportation Plan (NTP) should make the average driver pull over and take notice. The NTP lays out plans for so-called “road diets,” whereby some of the city’s busiest streets—such as Jackson—are slimmed from four lanes to three so that bike lanes may be incorporated. The NTP also seeks hundreds of thousands of dollars in funding for an additional 70 pedestrian crosswalks.

Critics shudder at the thought and say that 70 additional pedestrian crosswalks present exponentially more opportunities for those who use them to be injured or even killed.

“We’re doing pedestrian crosswalks on the cheap,” said a Council member, “and we’re paying for them in human lives.”

At the December 16, 2013 City Council meeting, Ward 4 Council member Jack Eaton said: “Pedestrian safety requires doing it right, not hurrying or being cheap.”

In December 2013, in response to citizen complaints, a rise in pedestrian-vehicle accidents and a pedestrian death on Plymouth Road, six City Council members, including Eaton, voted in support of a resolution to amend the pedestrian crosswalk ordinance in such a way that it would have been essentially repealed.

Their effort was thwarted when Mayor John Hieftje vetoed the resolution.

That controversy aside, the 2013 NTP offers up not only a variety of proposals concerning walking and biking within the city, but also data that reveal improvements referred to as “critical” in the city’s first (2007) NTP remain unmet after six years.

“The City of Ann Arbor’s Non-motorized Plan identified the critical need to expand the city’s infrastructure by adding 82.5 lane miles of on-road bicycle lanes, 25 miles of sidewalks, and 130 mid-block crossings,” reads the city’s website.

From miles of bikes lanes to sidewalks and from “pedestrian facilities” such as crossing islands and flashing beacons to bike roadways, Ann Arbor’s NTP failed to meet multiple non-motorized transit goals set forth in 2007.

Since 2007, 36 miles of bike lanes were added—that’s lane miles. A lane mile is calculated by measuring the length of roadway with bike lanes and multiplying it by the number of bike lanes. For example, one mile of road with a bike lane on one side of the road measures as one mile. A mile of road with bike lanes in both directions measures as two miles.

The 2007 NTP called for the addition of 25 miles of sidewalks. Only 3.4 miles of sidewalks have been added since 2007.

The 2007 NTP called for the addition of 105 pedestrian facilities, including major and minor crossings. Only 38 (31 major and 7 minor) crossings were completed.

The only 2007 goal that was surpassed was the proposed 2 mile addition of shared use path. Between 2007 and the presentation of the 2013 NTP to Council, 2.2 miles of shared use path were built along Washtenaw Avenue.

So while the number of trips made by residents riding bicycles increased, as anticipated in the 2007 NTP, the recommended 25 miles of bike routes were never installed. Bike routes create safe, separated facilities for cyclists.

Several of the Council members who approved the 2007 NTP still serve. They include the Mayor and Mayor Pro Tempore Ward 4 Council member Margie Teall, Ward 1 Council member Sabra Briere and Ward 5 Council member Mike Anglin.

The 2007 NTP replaced the city’s bicycle master plan, which was then incorporated into the city’s master plan, and called for implementing corridor-specific infrastructure improvements. Work began on developing the 2007 plan in early 2004, and included public workshops and professional city planning input. The Downtown Development Authority and the University of Michigan each contributed $20,000 to the planning effort.

The City of Ann Arbor’s website incorrectly claims:

“The City most recently reaffirmed its commitment to complete streets with the adoption of the 2009 Transportation Master Plan Update, the dedication of 5% of the City’s Act 51 funds for non-motorized transportation projects, and the requirement to include non-motorized elements in all road construction projects….”

In 2009, however, Council members voted to reduce the percentage of Act 51 funding given over the non-motorized transportation from 5 percent to 2.5 percent. Members on Council at that time still serving in city government include John Hieftje, Sabra Briere, Christopher Taylor, Margie Teall and Mike Anglin. DDA Board president Sandi Smith served on City Council in 2009, as well.

Since 2010, the amounts allocated for alternative transportation have been as low as $181,000 and as high as $745,000. In the 2013 budget, $448,000 is set aside for alternative transit projects.

The nonprofit Washtenaw Biking and Walking Coalition, a small advocacy group, has pushed to have non-motorized transit fully funded. In May of 2013, in response to complaints from the WBWC, John Hieftje told the former AnnArbor.com “It’s true the city did scale back the percentage going to alternative transportation in recent years because more money was needed for road maintenance.”

Road maintenance, however, is not paid for out of the Alternative Transportation Fund, but rather from the Street Repair Fund. That fund collects between $8-$11 million dollars through an annual dedicated millage paid by taxpayers.

It’s not clear that even with more money the goals set forth in the 2007 NTP would have been met.

One of the largest expenditures in the Alternative Transportation budget from which the non-motorized transportation funds are taken is city transportation manager Eli Cooper’s salary and benefits. In addition, money from the Alternative Transportation Fund has been used to pay for designs and other costs associated with the effort to build a new $45 million dollar train station.

Cooper serves on the Board of the AAATA, and Ward 3 Council member Stephen Kunselman has repeatedly suggested that Cooper should resign so as to devote his time exclusively to non-motorized transit issues.

The recently approved Five-Year Solid Waste Plan revealed similar problems with unmet goals. Ann Arbor residents were told single-stream recycling would double collections (it didn’t) and save taxpayers millions over the next 10 years (revenues from the sale of single-stream baled materials have fallen).

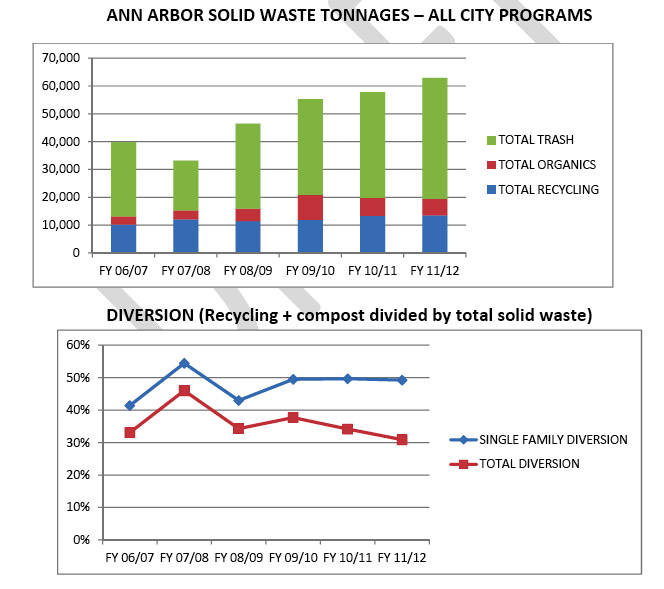

According to the Five-Year Solid Waste Plan, the number of tons of material sent to the city’s landfill has risen significantly since 2010. In addition, single-family diversion rates remain stalled at 50 percent, where they were in 2006, when residents paid just half of what they pay now for solid waste service.

Most importantly, say some local environmentalists and City Council members, the Solid Waste Plan revealed the city’s overall diversion rate plummeted from 40 percent in 2009 to 30 percent in 2012.

In July of 2011, it was revealed that single-stream collections projections made by consulting company RRS, which employs long-time Ann Arbor Environmental Commissioner David Stead, were off by some 40 percent. Tom McMurtrie, Solid Waste Coordinator for the City of Ann Arbor told the media, “the actual tonnage collected is still a 20 percent increase over the number of tons that were collected in the previous year with two-stream recycling.”

In 2002, shortly after Mayor Hieftje took office, officials announced a goal of diverting 60 percent of solid waste collected from the landfill. Eleven years and almost $100,000,000 million solid waste tax dollars later, the city’s most recent Five Year Solid Waste Plan “Waste Less” revealed:

“The city’s (2002) diversion goal of 60 percent has not yet been reached, as the single-family diversion rate remains around 50 percent.”

To be fair, a diversion rate above 40 percent is laudable. However, the drop in total diversion to 30 percent puts Ann Arbor at the bottom of the recycling food chain.

There is one area where there has been a dramatic increase with respect to recycling: the amount of money spent to pay Recycle Ann Arbor to haul recyclables. That amount has skyrocketed since 2004, when the City of Ann Arbor granted the non-profit a 10-year no-bid contract.

That contract called for the City to pay Recycle Ann Arbor $766,000, according to minutes from the December 15, 2003 City Council meeting. Ann Arbor taxpayers pay for the trucks, fuel, and repairs of Recycle Ann’s Arbor’s collection vehicles.

By 2008, the cost to taxpayers to have Recycle Ann Arbor haul virtually the same number of tons of material to the MRF that the company hauled in 2003, had risen from $766,000 to a whopping $1.6 million dollars. When the 2012 contract was implemented and RAA came up short, City Council members approved an additional 10 year $10 million dollar pay out to Recycle Ann Arbor.

Like the 2007 NTP, the city’s recently adopted Five-Year Solid Waste Plan reveals Ann Arbor is still struggling to meet environmental goals set forth almost a decade ago. In other words, the “new” non-motorized transportation plan, as well as the “new” solid waste plan are little more than leftover goals repackaged with new capital improvement requests, such as the proposed multi-million dollar Materials Recovery Facility (MRF) in the Solid Waste Plan and in the NTP bike stations with showers.

The NTP and Solid Waste plans—both present and past— reveal a pattern. Over the past seven years, under the direction of long-serving city staff who are some of the most generously compensated in the state, Ann Arbor has not met many of the ambitious environmental goals on which local elected officials have ridden to re-election.

Instead, city staff have crafted ambitious long-range plans the existence of which Ann Arbor’s Mayor and Council members have used for their own political purposes—even as they failed to adequately finance the NTP, according to criticisms levied by leaders of the Washtenaw Biking and Walking Coalition on the group’s website, and objectively assess the goals of the Solid Waste plan.

“If we set goals, we need to meet them,” said one Council member.

Environmentalism in Ann Arbor has fallen victim to what one member of the Environmental Commission referred to as a decade of “greenwash.”

“If our elected officials and City Administrator focus on measurable outcomes, we will have a city that is really bike and pedestrian friendly,” said the Environmental Commission member. “Over the past seven years, we could have met many of those goals. It’s about talking the talking and walking the walk. Ann Arbor can do better. I know we can.”