ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT SHOULDN’T be predicated on which of Ann Arbor’s 21 public elementary schools a child attends. The AAPS elementary curriculum is standardized throughout the District, and teachers are uniformly compensated, qualified, supported, trained and supervised, thanks to a union contract. However, analyses of MEAP scores going back to 2009 reveal that at the same three Ann Arbor elementary schools, over 40 percent of fifth graders repeatedly demonstrated advanced mastery of the MEAP subjects tested. Those subjects include reading, mathematics and science.

Meanwhile, at a group of six elementary schools fewer than 10 percent of students demonstrated advanced mastery of the subjects tested by the MEAP. This pattern has repeated itself since 2008. At Mitchell Elementary, in the time it took a student to advance from first to fifth grade fewer than 10 percent of fifth grade students demonstrated advanced mastery of reading, mathematics and science each year. During the same period, at King Elementary School in each of those years more than 40 percent of fifth graders demonstrated advanced mastery in one or more of the subjects tested.

While District officials focus on the percentage of students who are “proficient,” it is the percentage of students who test at advanced levels that lays bare a pattern of pernicious under-performance that has impacted approximately 2,000 students at the six elementary schools where fewer than 10 percent of fifth graders tested at the advanced level over the five year period.

Studies have drawn direct correlations between advanced scores on tests such as the MEAP, and being able to predict high school GPAs. According to one study, “scores in the Advanced ranges from each MEAP category yielded an excellent accuracy rate for predicting a GPA of 2.5 & above, and a strong accuracy rate for predicting a high school GPA of 3.0 & above. The Mathematics and Reading categories demonstrated an excellent prediction success rate for the GPA category of 3.5 & above.”

Sometime toward the end of March 2014, the Michigan Department of Education will release MEAP scores for the state’s elementary and middle schools. The data is a treasure trove for those who enjoy sifting through such information. Test scores impact districts’ curricula and often determine what a particular school will focus on academically. For example, a school with high numbers of students who test as “not proficient” in writing will develop curricular programs and strategies to deal with the problem.

MEAP scores reveal that not only are significant achievement gaps a problem between Ann Arbor elementary schools, huge gaps have been reflected in the academic performance of students at the same small group of elementary schools since 2008.

The Ann Arbor Public Schools collects $.28 cents of every property tax dollar paid, and, together with state money, spends about $12,000 per year educating each student. Schools in Washtenaw County spend more than $500,000,000 dollars each year to educate 50,000 students. As it turns out, in Ann Arbor and Washtenaw County, like in most districts around the county, relatively little of that money is spent on figuring out which teachers are effective and why.

This, in part, is why it’s possible that two elementary schools in Ann Arbor, King and Mitchell—schools that are less than 15 minutes distant from each other by car—have student outcomes that are miles apart.

There is a debate raging nation-wide about whether teacher compensation and even continued employment should be predicated (in whole or in part) on student test scores.

In Los Angeles, the newspaper stunned District parents and infuriated the leadership of one of the largest and most politically powerful education unions in the country, the United Teachers of Los Angeles, by compiling and analyzing several years of test scores, matching up the test scores with the individual teachers in the District and putting a searchable database of the information online. Parents (or anyone) could type in the name of a teacher, and see whether students taught by that individual showed progress as measured by standardized tests administered by the State of California.

The original August 2010 article on The L.A. Times web site was been shared over 7,000 times on Facebook since it was published.

The article begins: “Yet year after year, one fifth-grade class learns far more than the other down the hall. The difference has almost nothing to do with the size of the class, the students or their parents. It’s their teachers. Seeking to shed light on the problem, The Times obtained seven years of math and English test scores from the Los Angeles Unified School District and used the information to estimate the effectiveness of L.A. teachers — something the district could do but has not. The Times used a statistical approach known as value-added analysis, which rates teachers based on their students’ progress on standardized tests from year to year.”

The article enraged the local teachers’ union leaders, who launched a boycott of The L.A. Times, and demanded that the paper take down the searchable database. It’s easy to see why the union leaders became upset. The article doesn’t mince words:

In Los Angeles and across the country, education officials have long known of the often huge disparities among teachers. They’ve seen the indelible effects, for good and ill, on children. But rather than analyze and address these disparities, they have opted mostly to ignore them. Most districts act as though one teacher is about as good as another. As a result, the most effective teachers often go unrecognized, the keys to their success rarely studied. Ineffective teachers often face no consequences and get no extra help.

Value-added analysis rates teachers based on their students’ progress on standardized tests over a number of years. According to The L.A. Times’s article, “A student’s performance is compared with his or her own in past years, which largely controls for outside influences often blamed for academic failure: poverty, prior learning and other factors.”

It is a tool favored by those in the school reform movement in the United States, as well as by the Obama administration. It is a tool that is not embraced by the national leadership of the American Federation of Teachers though AFT President Randi Weingarten has been more open to the use of value-added analysis than any of her predecessors. Interestingly, in March 2011 The L.A. Times reported that the teachers’ union was preparing to move forward with its own “confidential” value-added rating system, and the school board was planning to move forward to use value-added analyses in evaluating the district’s 6,000 teachers.

However, another of the AFT’s affiliates, this time the powerful New York United Federation of Teachers—where the past several AFT national presidents have come up through the ranks—is fighting the public release of value-added ratings for 12,000 K-12 teachers there.

AAPS officials said they do not use value-added analysis to evaluate their 1,100 teachers though the District does track the student MEAP results of each of the District’s teachers. MEAP scores released by the state give one-year snapshots of how schools and school districts are doing with respect to teaching math, reading, writing, science and social studies. As in Los Angeles, and of course school districts in states across the country, there are significant disparities within the Ann Arbor school district with respect to student performance on the state’s standardized test. There are testing achievement gaps between students of different races, grade levels and, most disturbingly, between schools.

The gap between Ann Arbor’s elementary school students testing at the advanced level is persistent and reflected in MEAP data made available by the Michigan Department of Education as far back as 2004.

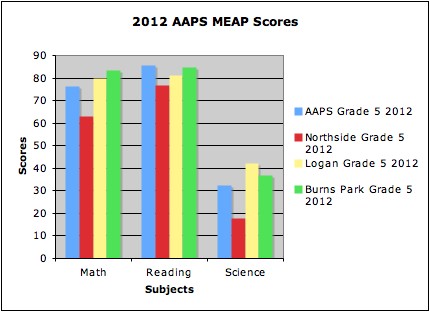

The 2010 and 2012 MEAP Score graphs, above, present snapshots of fifth grade MEAP results at three Ann Arbor elementary schools. The schools, Northside Elementary and Logan Elementary, are located 1.5 miles apart, geographically. Both schools feed into Clague Middle School. In 2010 and 2012, there were significant differences in the achievement of the students in 5th grade at Logan and Northside. Percentages reflect the number of students tested who scored at the “Proficient” level in the subjects. The AAPS scores are the District-wide percentages of students scoring at the “Proficient” level in the subjects tested.

There are achievement gaps between the students tested at the three schools. Only the students at Burns Park Elementary exceeded District-wide MEAP scores in each of the subjects and both of the years sampled. Logan student MEAP scores exceed 2010 and 2012 District-wide MEAP scores. Conversely, students at Northside Elementary didn’t meet or exceed District-wide scores of students who tested at the Proficient level in any of the subjects tested in either of the years sampled.

A look at the graphs, as well as the table, below, shows that at Northside Elementary student achievement at the Proficient level has lagged behind that of students at nearby Logan, and Burns Park Elementary Schools, as well as students District-wide. In 2008 and then again in 2011 and 2012, fewer than 10 percent of Northside fifth graders demonstrated advanced proficiency in mathematics and/or science.

One important fact to remember is that these MEAP scores represent the achievement of the previous academic year. In other words, MEAP scores of fifth graders represent the mastery of work done in the fourth grade, not the fifth grade. Fifth grade teachers are allowed to spend several weeks on MEAP prep. prior to the October test, but that work is meant as a refresher course, as it were.

Why are there such noticeable differences in the achievement of students at the elementary schools? Ann Arbor officials have, in past, used race as an explanation. Demographic data collected during the 2010 head count—the most recent data made available by the AAPS—show that while 70 percent of Burns Park Elementary students were white, only 42.7 percent of King Elementary students were white. That’s just a slightly higher number than the percentage of white students enrolled at Carpenter Elementary (38.7 percent). The table, below, shows that at Carpenter Elementary between 2008 and 2011 fewer than 10 percent of students tested at the advanced level in mathematics and science. Those same years, at King Elementary, over 40 percent of the fifth graders tested scored advanced in mathematics and science.

| Year | School | Subject | Percent Students Advanced |

| 2012 | King | Reading | 61.8 |

| Angell | Mathematics | 54.8 | |

| King | Science | 40.8 | |

| 2011 | King | Reading | 44 |

| Angell | Mathematics | 50 | |

| Angell | Science | 38 | |

| 2010 | Burns Park | Reading | 47.9 |

| King | Mathematics | 46.1 | |

| King | Science | 44.7 | |

| 2009 | Burns Park | Reading | 54.6 |

| King | Mathematics | 55.3 | |

| King | Science | 35.1 | |

| 2008 | Angell | Reading | 60.9 |

| Thurston | Mathematics | 44.1 | |

| King | Science | 46 | |

| Year | School | Subject | Percent Students Advanced |

| 2012 | Mitchell | Reading | < 10 |

| Mitchell | Mathematics | < 10 | |

| Mitchell, Northside, Pattengill, Pittsfield | < 10 | ||

| 2011 | Mitchell, Pittsfield | Reading | < 10 |

| Mitchell, Pittsfield | Mathematics | < 10 | |

| Carpenter, Mitchell, Northside | Science | < 10 | |

| 2010 | Pittsfield | Reading | < 10 |

| Carpenter, Mitchell, Open, Pittsfield | Mathematics | < 10 | |

| Abbott, Carpenter, Mitchell, Pattengill, Pittsfield | Science | < 10 | |

| 2009 | Mitchell | Reading | < 10 |

| Carpenter, Mitchell, Open, Pittsfield | Mathematics | < 10 | |

| Mitchell, Pittsfield | Science | < 10 | |

| 2008 | Mitchell | Reading | < 10.8 |

| Carpenter, Mitchell, Open, Northside, Pittsfield | Mathematics | < 10 | |

| Allen, Carpenter, Mitchell, Dicken, Pittsfield, Pattengill | Science | < 10 |

Looking at state data that identify which Ann Arbor elementary schools have the most students who qualify for free and reduced price lunch suggests that socioeconomics plays a significant role in the district’s elementary school achievement gap and its persistence. At King Elementary, in 2012 just 7 percent of the school’s 446 students qualified for free lunch, down from 8 percent in 2008. Meanwhile, at Carpenter Elementary, 35 percent of the school’s 386 students qualified—up from 30 percent in 2008.

While Ann Arbor is by no means a low socioeconomic status (SES) school district, it has a cluster of six elementary schools where lagging student achievement suggests the elementary schools suffer from problems that plague inner-city schools and schools located in poor communities. Research indicates that school conditions contribute more to SES differences in learning rates than family characteristics:

- Schools in low-SES communities suffer from migration of the best qualified teachers, and low educational achievement.

- A teacher’s years of experience and quality of training is correlated with children’s academic achievement. Yet, children in low income schools are less likely to have well-qualified teachers.

When AAPS officials present MEAP data, officials don’t make comparisons between individual schools, but rather make comparisons between how the students performed in each grade level. One other way that the gap is masked is in the fact that there is a tendency to lump together the students who met or exceeded expectations. There is, of course, a difference between simply meeting expectations and achieving at an advanced level.

This comes from the Academics section of the AAPS web site: “Over 96% of third graders, 94% fourth graders and 93% seventh graders met or exceeded state standards in math.”

National education reformers seek to link consistent under-performance such as that reflected in Northside’s MEAP data, to individual teachers, who can then be mentored or replaced. National reformers also seek to replicate student achievement, such as that reflected in the advanced level MEAP scores at King Elementary School, throughout individual districts.

Ann Arbor Public School MEAP data suggest that depending on which elementary school a child is enrolled in within the AAPS will determine whether the child simply “meets” state standards (is proficient) or will master the material at an advanced level.

To lump the “met or exceeded” groups together effectively disguises the reality that a parent who sends her/his child to one school rather than another could see significantly varied achievement results. Students will be more likely to demonstrate higher achievement if enrolled at King or Angell Elementary Schools, according to MEAP data. Yet, elementary schools where students are more likely to master reading, science and math at an advanced level are not selected to participate in the AAPS School of Choice program.

Many of the elementary schools of choice are those with achievement scores in reading, math, science and writing that have, since 2008, been significantly lower than those of students who attend King, Burns Park and the Angell Elementary Schools.

Is race to blame for Ann Arbor’s achievement gap, as AAPS officials suggest? The investigative and extensive analysis work of The Los Angeles Times suggest that when one class, group or school of students learns far more than another in a school district, the difference has almost nothing to do with the size of the class, the students or their parents.

The L.A. Times published a follow-up story on value-added analysis that asks just this question. In that piece, it was suggested that, “Theoretically, value-added models inherently account for these differences [race and poverty], because each student’s performance is compared each year with the same student’s performance in the past, not with the work of other students. But many experts say further statistical adjustments are necessary to improve accuracy.”

In August, shortly after she was hired, AAPS Superintendent Dr. Kerr Swift briefly spoke about the achievement gap. It was reported that she charged teachers to “roll up their sleeves” to tackle graduation rates below the 80 percent accountability requirement among African American, Hispanic and economically disadvantaged students.

Dr. Kerr Swift has also said this about the achievement gap in the district she leads: “We must be courageous and confront and embrace the challenges that lie ahead of us. We will meet our challenges, particularly in the areas of student discipline where we have seen progress.”

However, recent studies have debunked the theory that focusing on the so-called “discipline gap” to help close the achievement gap works. On the contrary, the discipline gap strategy often results in sky high susspension rates of black students. In Berkeley, California, where officials implemented a “discipline gap” strategy three years ago, 60 percent of all the suspensions given were of black students, even though they make up just 20 percent of the student population. In Ann Arbor, 42.2 percent of the 1200 students suspended in 2012 were black, and black students made up about 15 percent of the total student body.

While the district’s achievement gap at the proficient level has narrowed slightly, the gap at the advanced mastery level in 5th grade students persists. Thus far, officials have not outlined any strategies to deal specifically with the achievement gap at the advanced level of mastery, despite research that suggests that doing so could help bump up graduation rates among African American and Hispanic students in the Ann Arbor Public Schools.