School Board Member and Wife Took County Grant Money For Which They Were Ineligible

by P.D. Lesko

County records show Ann Arbor School Board Trustee Ernesto Querijero, through his wife Lisa Querijero, applied for funding from the Washtenaw County Community Priority Fund in 2022. The money, according to the application filled out and signed by Lisa Querijero, was for Books for Kids. Books for Kids, which the Querijeros say they run, takes donations of books and money and has, according to their website, distributed books “to under-resourced schools in the Philippines.” The Community Priority Fund applications required those who requested funding to do so on behalf of a business or a non-profit.

State and federal tax records show Books for Kids is not a non-profit registered with the IRS or the State of Michigan. It is not registered as a business, either.

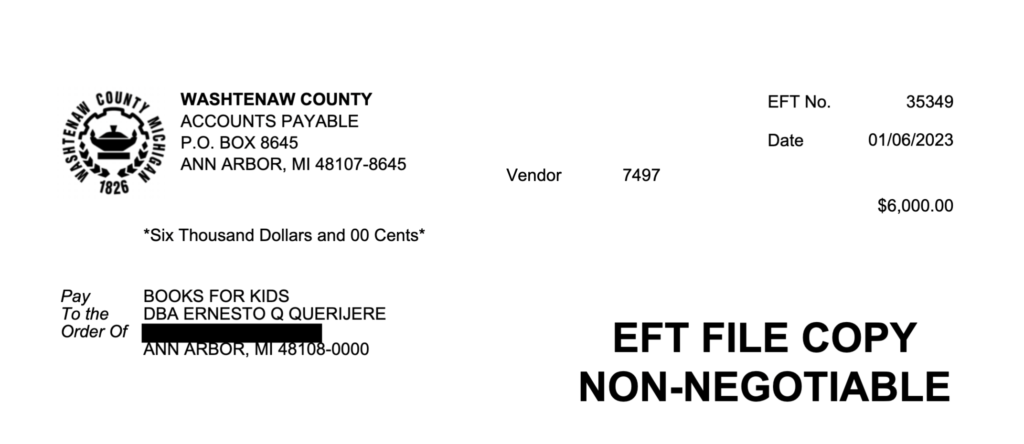

As a result, the check for the $6,000 grant was requisitioned and made out to “Books for Kids DBA Ernesto Querijero.”

In soliciting and accepting public funds for which the School Board Trustee was not eligible, he violated several sections of the AAPS School Board Member Code of Conduct.

The public money, for which the School Board Trustee was not eligible to apply or to receive, was handed over to him personally in Jan. 2023 by Alize Asberry Payne and County Administrator Greg Dill. Dill recommended to the County Commissioners seated in 2022 that they vote to give Trustee Querijero $6,000 in public money. The County’s procedures for evaluating CFP applications included, ostensibly, four levels of review with the final responsibility for approval squarely assigned to the County Commissioners:

Ann Arbor Public School parents upset at Trustee Querijero’s co-sponsorship of a resolution calling for a ceasefire to the war launched on Oct. 7, 2023 against Israel by Hamas terrorists living in Gaza, investigated the Querijero’s grant application, and the Books for Kids tax status. One of the parents in the group contacted the Ann Arbor Independent in early-April 2024. The newspaper, after confirming the Books for Kids ineligibility for the public grant money, sent an email to the Querijeros asking about the application, asking who approved their grant, and how the money was paid out.

Lisa Querijero responded: “If a box was checked wrongly, it was a mistake. This was the first grant Books for Kids ever received. I’m a hairdresser, so this is not my skill set, but helping people is. Up until then Books for Kids was self-funded. I applied for the grant as a grassroots organization, I never presented myself as anything else and I never have. I don’t know who approved the initial grant. I was surprised to receive it. l learned of the grant approval from reading the newspaper article and then received a check after that for $6,000. It was deposited into our account and spent within three months entirely on books from book depot online. I’m happy to send receipts.”

The grant application did not require Lisa Querijero to “check a box” identifying whether Books for Kids was a non-profit or a business entity. The application presented a yes/no question to determine whether the applicant was submitted on behalf of “an non-profit organization or a business entity.” [sic]

In addition to buying books, the grant money was to fund “10 Free Book Fairs in one year.”

No such events were listed between Jan.-Dec. 2022 on the Books for Kids’s website.

Officials from the Ypsilanti Public Schools, the Parkridge and Bryant Community Centers were contacted. None of them could not corroborate that any Books for Kids free books fairs took place.

On Apr. 24, 2024, an official at the Bryant Community Center in Ypsilanti when asked about Book for Kids Free Book Fairs said, “That is not an organization we have ever worked with.”

On Apr. 24, 2024, an official at the Parkridge Community Center, likewise, said there was no record of Books for Kids ever partnering with the Center to put on any free book fair.”

On April 8, 2024, Lisa Querijero sent a message through Facebook Messenger: “My husband sent you an email answering your questions. Please issue an apology for falsely accusing Books for Kids of improperly taking money. Thank you.”

Lisa Querijero expressed dismay at the grant having been discovered by AAPS parents. In a message sent through Facebook Messenger, she said, “Maybe the person who tipped you to inquire about my book project is the one who posted these flyers in my neighborhood. It was the same week.”

Lisa Querijero went on the say, “Our family is being harassed by you and by the person posting these flyers by my house, perhaps your working together” [sic].

The Querijeros were improperly awarded the public funds by the County’s Racial Equity Officer, Alize Asberry Payne. Records show her boss County Administrator Greg Dill signed off on the Querijero grant. The money given to Querijero was also approved by the County Commissioners.

The was another in a long list of examples of poor financial controls within Washtenaw County government, lack of employee oversight on the part of County Administrator Greg Dill, and mismanagement of public funds by County employees who are not held accountable by a defensive Board of Commissioners.

Ernesto Querijero, in response to questions about the grant, said that money the couple received for Books for Kids was reflected as income on their personal income tax returns. He also claimed that the $6,000 had come from the County’s “general fund.”

Public records show the $6,000 given Trustee Querijero for his personal use came from the County’s marijuana tax revenue received from the State of Michigan, not the Community Priority Fund. Emails obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests show Asberry Payne asked that marijuana tax revenue given to the County by the State of Michigan be transferred (without the knowledge or approval of County Commissioners or the public) to her control for use in funding Community Priority Fund grants.

The Querijeros offered no evidence that they had paid taxes on the $6,000 from the County or any donations. The Books for Kids website solicits donations through CashApp and Venmo. Ernesto Querijero said in an email that he and his wife, who launched Books for Kids in 2017, have taken in “$22 in donations.”

According to IRS officials, given the status of Book for Kids as neither a business, a DBA or a non-profit, money taken in by the Querijeros would have to be reflected as self-employment income. This would require payment of both Medicare and Social Security taxes.

Pervasive Lack of Oversight and Transparency

The County employee with whom Lisa Querijero said she interacted in pursuit of the $6,000 grant was Akintunde Oluwadare. Oluwadare was hired by Washtenaw County in May 2023 as an ARPA Project Manager & Compliance Specialist. In Sept. 2023, he became the Equity Program/Community Engagement Manager. Oluwadare is supervised by Alize Asberry Payne, the County’s Racial Equity Officer.

The Community Priority Fund grant program in 2022 was overseen by Asberry Payne and it still is. That same year, in June 2022, Asberry Payne recommended to the County Administrator that $1.2 million in federal ARPA fund money be awarded to a group called Supreme Felons, Inc. A child rapist and a murderer on parole had submitted a grant application peppered with falsehoods and fabrications.

Nonetheless, on Greg Dill’s recommendation, in July 2022 the Board of Commissioners awarded Supreme Felons, Inc. $1.2 million in taxpayer money to work with children in county schools and parks.

In May 2023, Supreme Felons Inc.’s tax exempt status was revoked by the IRS. Nonetheless, Asberry Payne, who is charged with the oversight of ARPA Fund grant applicants’ performance and use of the money, distributed over $50,000 per month in public money to the group, in violation of the contract between the non-profit and Washtenaw County.

In seeking an answer to why Alize Asberry Payne has consistently failed to handle and distribute public money legally and responsibly, the newspaper obtained her application for the County Racial Equity Officer I/II job she has, as well as her resume and personnel file. A fact check of the documents revealed that Alize Asberry Payne had included falsehoods and fabrications in her application materials.

Other public records revealed she has a decade-long track record of financial imbroglios. Alize Asberry (as she was known in 2013-2016) was a defendant in multiple lawsuits filed in the San Francisco Superior Court related to her theft of money from roommates, as well as non-payment of a large debt.

Via email, the newspaper asked both County Administrator Greg Dill and racial equity officer Alize Asberry Payne how a school board trustee, via a grant application submitted by his wife, obtained $6,000 in public money for himself through a grant program meant to fund only businesses and non-profits.

The two have not yet responded.

The newspaper also asked if the County Administrator intended to ask Querijero to return the $6,000. Greg Dill did not reply.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.