by P.D. Lesko

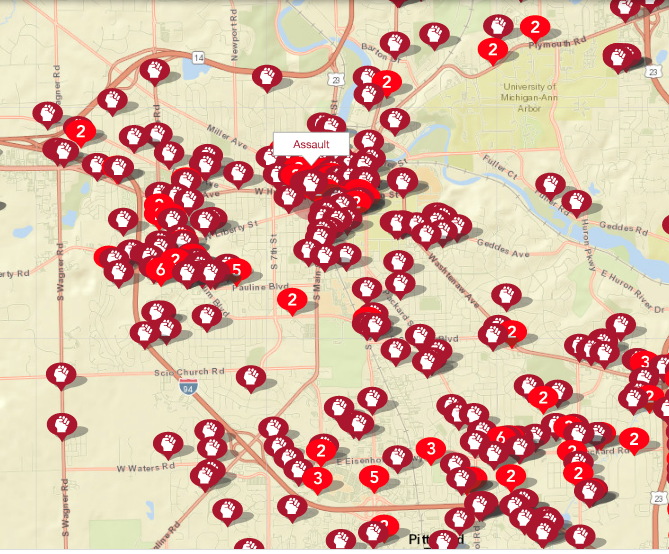

A search at Crimemapping.com shows that assaults/assaults and battery (misdemeanor and felony) are one of the most frequent crimes reported in Ann Arbor. The assaults reported included intimidation, stalking, use of a telephone to threaten, domestic assaults, and assaults where weapons were involved. Between April and September 2022, according to data reported by the AAPD to Crimemapping, the AAPD reported 532 assaults, 374 reports of fraud, 311 vehicle break-ins, 150 burglaries, 72 DUIs, 47 sex crimes and 21 robberies. Being assaulted and filing a complaint, means ending up in the County’s criminal justice system. The perpetrator faces more direct involvement, particularly if the plaintiff is the Prosecutor’s Office (the State of Michigan). The victim in such cases ends up less directly involved, but is nonetheless sucked into a criminal justice system that can be impersonal, confusing and difficult to navigate.

On December 23, 2021, I was the victim of a hate crime and an assault.

After the incident, we went home and called the AAPD. The desk officer took the report and asked me to email her the video. When Detective Steven Van Alstine contacted me in January 2022, he asked if I had any video evidence. I sent the video again. In a Jan. 31, 2022 email, Van Alstine told me that he had sent over his report to the County Prosecutor’s office “for review.”

The Prosecutor’s Office authorized charges in August 2022. Between Jan. and Aug. 2022, I called and asked to speak with the Asst. Prosecutor who was reviewing the case and was told twice that would not be possible. I know I could have used the Freedom of Information Act to track down the public employee who was reviewing my case, but decided not to.

In the meantime, a few weeks after the Dec. 2021 assault, the assailant again threatened us on a public sidewalk, after we’d crossed the street with our dog to avoid her. She spewed homophobic threats and comments. By chance, we ran into an AAPD officer on patrol, told her about the incident and the officer pulled up the original report. She said she would go to the assailant’s home and speak to her.

In September 2022, nine months after I reported the assault to the AAPD, I got a large envelope from County Prosecutor Eli Savit’s office. In his letter, Savit wrote that he had charged the assailant and that prosecution would proceed. There were various pamphlets outlining the Prosecutor’s Victim Advocate services program. I was also informed that the assailant’s attorney might contact me and that I had a series of options of support to help me speak to the assailant’s attorney. Frankly, I can’t wait to speak to the assailant’s attorney, and will do so with pleasure.

I filled out a form so that I would be apprised of the relevant court dates, and sent the form back to the Prosecutor’s Office in the postage paid envelope. There was a form which asked me to outline any money spent on remedying physical injuries. I asked to be contacted by email by the Prosecutor’s Office staff, including my assigned Victim’s Advocate, Meghan Spangler.

During the course of writing a series of articles about mismanagement of the County’s domestic violence shelter, SafeHouse Center, I had conversations with over a dozen victims of domestic violence (10 Black and 2 white) and listened to their difficulties navigating the criminal justice system, including and mostly especially, the Prosecutor’s Office. The domestic violence and assault victims whom I interviewed were unequivocal: Eli Savit and his staff were the flies in the ointment, the monkeys in the wrench, the reason why these women and their children continued to be terrorized, threatened, and their cases unresolved.

Without evidence, such stories are just that, stories. One victim, however, a mother of several children, was dogged, both with me, the Ypsilanti Police detectives working on her case, Eli Savit and his second in command, Victoria Burton-Harris. She emailed Savit directly (blind copying me), phoned him and begged Savit to use the phone recordings, photos, emails and crime reports that she had provided to prosecute the assailant stalking her and threatening her children. First, the YPD detective lost the evidence (and was subsequently fired). The next detective said the evidence and charges had been sent to Savit’s office. He provided the victim proof of this.

The woman then invited me to a three-way call. Muted, I listened and took notes as Eli Savit, with a shocking lack of empathy, recognized the woman and her case immediately. He fumbled around on his computer for a moment looking for the YPD records related to her many complaints against the stalker, including sreenshots of texted threats, and voice recordings of threats against the lives of her children. After a few moments, Savit sighed and said he couldn’t find the woman’s records; they had not been received. He suggested the woman go back to the YPD and ask the detective to (again) send the records to Savit’s office. I texted the victim mid-call and suggested she ask Savit to have his own office contact the YPD directly. She asked and Savit, after a long pause, grudgingly agreed to do so. Not a single time during the phone conversation did Savit apologize for his office’s mistakes or acknowledge the woman’s suffering and fears for her safety and that of her young children.

This victim’s journey began in August 2021. In June 2022, she texted me to say that her assailant was found guilty of stalking. She said the Court had issued a bench warrant and that the police were looking for the man. In the interim, she had moved three times and spent hours and months begging public officials in the Washtenaw County criminal justice system for protection and help. Ten months of terror, threats, Keystone Kops and a County Prosecutor’s office that has an average two-star rating on Google.

A few days ago, while searching the 15th District Court cases online, on a whim I looked up the name of my assailant. She was scheduled for arraignment in two days. Arraignment is all at once critical and perfunctory. A plea is entered. Fingerprinting is ordered (if necessary). Bond and bond conditions are set. A date for a pre-trial hearing is scheduled.

I called my Victim’s Advocate to ask why I had not been emailed about the hearing. Her answer was at first that “no one shows up for arraignment.” What? Miss your arraignment and you’ll find yourself the star in a bench warrant, complete with a trip to jail, should you be snagged during a traffic stop. Of course some people don’t show up, but in the courtroom where my assailant’s arraignment happened, all of those called to appear were there. This included a man checking in from the jail who lost his temper during his arraignment and gave the non-plussed judge, Tamara Garwood, an earful before storming off camera. The Advocate then informed me that she had “too many cases” to apprise victims of their assailants’ arraignments and that she didn’t get arraignment information from the 15th District Court.

When I spoke to the 15th District Court Administrator, Shryl Samborn was polite and unequivocal: the Victims’ Advocates have access to the Court’s docket and case resources, whether the hearing is for an arraignment or sentencing. If victims’ are not being apprised of arraignments, it’s not because the information is unavailable to the Prosecutor’s Office or its Victim’s Advocates.

Here’s why the arraignment is critical to a victim: The judge gave my assailant a PR bond (personal recognizance) after instructing her to have no contact with either me or my partner. The judge asked my assailant if she owned a gun (no) and instructed her that she was not permitted to buy a gun, drink, do drugs, use marijuana, or go anywhere near where we live or worship. Violate your bond conditions and you’ll end up back in front of the judge who trusted you to adhere to those bond conditions.

Now imagine a victim of a more violent or serious crime, such as rape, felony assault or domestic violence. Would that victim have a vested interested in knowing if her/his assailant were released? Of course.

I’ll let you in on a secret. Eli Savit, after his election, instituted a policy whereby for those accused of domestic violence the Prosecutor does not routinely request bond; rather, most domestic violence assailants who are charged with assault are quickly (and quietly) released back into the community after arraignment, a community that includes their victim(s). This political decision means that our County judges, themselves elected officials, have to assume all of the political risk, moral responsibility (and blame) when imposing (or not imposing) a bond.

Research shows that it’s a life or death decision for a judge to give bond to a domestic abuser. In 2019, nine out of 10 murdered women were killed by men they knew, according to the Violence Policy Center (VPC), a national think tank. In nearly two-thirds of those cases the women were wives or other intimate partners of the men. In 2019, Black women and girls were murdered at a rate more than twice as high as white women and girls, according to the Washington-based VPC, which bases its figures on FBI data.

In my case, while the assailant lives two blocks from our house, she told Judge Garwood she has no idea where we live. Moments after the arraignment concluded, an email from Meghan Spangler appeared in my inbox.

Good morning,

The above-named defendant was arraigned this morning. The first pretrial is set for October 12th, 2022, at 9am, Judge Perry presiding. You do not need to be present for that hearing, below is a YouTube link in case you would like to watch the hearing. I will send an email with an update after that hearing.

At arraignment, the defendant was given a $5,000 PR Bond with standard conditions. The magistrate also added a no contact order for you and for Marjorie. There is also a No-Go-To Order for the home, places of employment, school, or worship for both you and Marjorie.

Please let me know if you have any questions.

Three observations:

- While the “first pre-trial” is set for 9 a.m., Judge Perry’s courtroom, Zoom link and docket will have at least half a dozen and, perhaps, as many as a dozen other cases scheduled for that day at 9 a.m. While Zoom has revolutionized this process, it’s still a matter of showing up at 9 a.m. and waiting, perhaps as long as three hours (if the judge shows up on time), until one’s case is called. Generally, those called to appear who are incarcerated will have their cases called first. This is a critical bit of information that Ms. Spangler neglected to explain. Scheduling issues like this are important to victims who take time from work to appear and who (rightfully) believe that a 9 a.m. appearance will happen at 9 a.m.

- An explanation of what, exactly, a “pre-trial hearing” is should absolutely be included as a part of the Prosecutor’s communication to victims. “A pretrial hearing has three objectives: First, it provides an opportunity for an early resolution of the case without a trial or to narrow the issues for trial. Secondly, this hearing is used to establish time frames for discovery, to exchange witness lists, and to file motions.” If motions are filed, the judge will then schedule another hearing, often two weeks later. The pre-trial hearing step can last for weeks, or the case can be resolved quickly. Ninety-five percent of criminal court cases never go to trial.

- $5000 PR bond with “standard conditions.” I know the conditions, because I watched this arraignment (and have watched many others). Ms. Spangler knows the standard conditions because she works in the Prosecutor’s office. The “standard conditions” should be explained clearly, especially because one of the “standard” conditions is that the PR bond is predicated on the assailant not possessing or purchasing a firearm. Thanks to Mr. Savit’s new policy, an assailant who commits an assault with a firearm or other deadly weapon would (most likely) be quickly released back into the community.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.