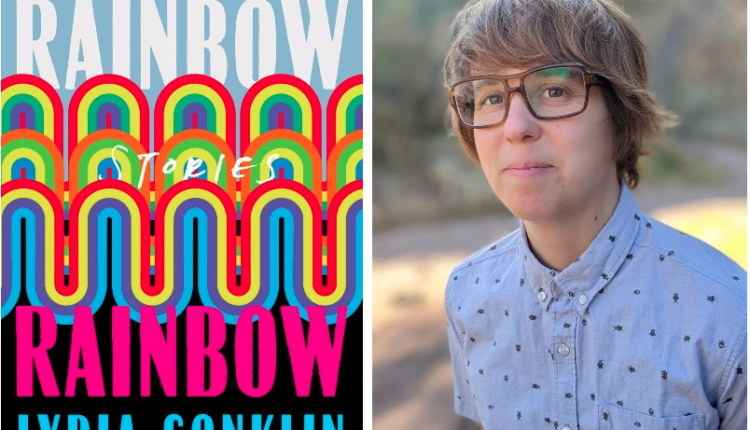

The Pleasure Principle: The Characters in Lydia Conklin’s Short Story Collection “Rainbow Rainbow,” Seek Gratification and Identity

by Martha Stuit, Pulp

Characters in Lydia Conklin’s Rainbow Rainbow perch on the precipice of something—a decision, a change, the start or end of a relationship, or even the dangerous cliff above a quarry where people swim and occasionally fatally fall.

Each story in this collection probes personal boundaries and desires to see how far the characters will stretch and when they will run in another direction. Queer, trans, and gender-nonconforming identities inform these stories as well as the book title, which is not only the name one of the story but also an Easter egg in one of the other tales, which reveals the meaning of the appellation Rainbow Rainbow.

Conklin is the Helen Zell Visiting Professor in Fiction at the University of Michigan and they will be an assistant professor of fiction at Vanderbilt University this fall.

Throughout the large—and small—turning points the characters face, they seek out their own needs and endure the pain of loss or the fulfillment gained. When distance grows between lesbian partners living in Wyoming, one of them grasps the extent to which their connection has deteriorated because the other was secretly pursuing her passion. On recognizing the shift, the narrator shares, “The words sent a crack of pain down my neck. We’d drifted so far apart. I’d failed to recognize creative euphoria in my own partner, living beside me in the middle of nowhere for three months. What was wrong with me?”

The beginning of the end had already begun.

In “Pioneer,” fifth-graders reenact the Oregon Trail journey at their elementary school in a highly anticipated activity. Coco opts to be an ox instead of the matriarch of a family, and “Coco wondered if she actually was an animal. That explained why she did not feel like anyone else at school. She certainly wasn’t normal.” While bearing the difficulties on the trail, such as a teacher popping out of the woods to assign illnesses and the degree of their severity, plus the budding cruelty of peers, Coco’s expedition becomes not just acting but the realization and start of embodying herself, beginning with rejecting her name.

Animals take on roles in the stories, too, including a tragedy involving a German Shepherd, squirrel, and ice. Ferrets serve as companions and distractions in “A Fearless Moral Inventory.” Yet, sex-addicted Carla fails the very creatures who are helping her, as “She lifts Boo high into the air. His head wags loosely on his body. When he reaches her face, he opens his mouth. He’ll bite if she draws him closer.”

Comfort is not without a sharp edge.

A frequent choice presented to the characters is whether to stay or go—and refreshingly, the characters usually choose what they want, not what will please others. While their self-regard causes moral quandaries, the elation of choosing themselves surpasses the agony of hiding who they are. As Heidi reflects in “Ooh, the Suburbs,” “She’d tell herself that leaving was right, that Kim liked her too much, that she’d only get hurt. But in all the lonely years ahead, she’d never be sure if she was just being cruel.”

Cruelty and freedom intertwine and become inseparable—what one person wants may not be what the other does.

I interviewed Conklin about their new collection, writing life, and time in Ann Arbor.

Q: Tell us about your time in Ann Arbor as the Helen Zell Visiting Professor in Fiction at the University of Michigan.

A: It’s been so wonderful to be here. I love the program so much. The MFA students are at the top of their game in fiction, and the faculty is very supportive. I have a writing group that I helped form here that has been such a literary inspiration to me. This is my second time around in Ann Arbor—the first time was from 2014-2015 when I was a lecturer in the writing department—and I feel now like it’s a home for me. I’ll miss it a lot.

Q: What does your new position at Vanderbilt University involve?

A: I’m so excited to get started at Vanderbilt—it’s a dream come true to have this job. I’ll be an assistant professor of fiction, working with their amazing faculty there and teaching undergraduate and MFA level fiction writing workshops, and probably some graphic fiction as well.

Q: How do you start writing a short story?

A: The beginning always looks different for me. Sometimes I base a story around an anecdote, like with “Boy Jump” it started with the news of the boy jumping off the cliff outside of Krakow, and then I built in my personal experience with gender and living in Poland. Other times I start with an idea, like wondering how anyone ever decides to have or not have children, as in with “Laramie Time.”

Q: How did your stories coalesce as your collection, Rainbow Rainbow?

A: The stories in the book took 12 years to complete. By the time I had enough breadth and diversity of experience and identity in my stories to have a book, I had dozens and dozens of stories I had to discard, either because they didn’t speak as well to each other or because they covered ground that was too similar to other stories. I worked with my agent and editor to pick an order for the stories, and to exclude some strong contenders that ultimately didn’t make the cut.

Q: One aspect of Rainbow Rainbow that I found particularly riveting is how characters do what they want and follow their desires—they are not people pleasers. In “The Black Winter of New England,” Hazel sneaks out and worries about it, as:

… she’s been careful to follow [her father’s] rules. Now she’s broken one so easily. Loneliness sweeps her. No one’s watching. When she snaps through the crust of snow and walks away from the house, a chill tickles her. She shouldn’t be allowed to just leave.

Is choosing oneself over what others want a common characteristic across the stories, or would you describe it otherwise?

A: That’s such an interesting observation! The way I think about it, many of the characters in the stories have reached a point of crisis—they have gone for different amounts of time understanding, subconsciously, something about themselves; sometimes their true gender identity or sexuality, other times that a relationship is over or that their sobriety is too tenuous to hold—and they have reached a moment where they no longer can or want to hold that knowledge inside. Facing that knowledge means people will be upset with them, but they’re past the point of people-pleasing. I think these moments are very fertile, dramatic ground for short stories to explore.

Q: The decisions the characters make—whether about their relationships, identities, or actions—bring discomforts and hurdles. In “Sunny Talks,” Sunny’s aunt must live with the aftermath of disclosing her identity. In “Boy Jump,” Daisy anticipates divulging the plan to become a trans man, and along the way, faces various indignities, such as “a queer-friendly bathing suit that promised to suck flat all the lumps of the female form, but only so much could be asked of any fabric.” How do you get to know your characters and what they will do?

A: In order to live in a way that’s true to themselves, the characters must face all manner of humiliations and hurdles, and behave in ways that are not always in line with their moral codes. The hardest time I ever have with my characters is when they’re behaving in ways that are morally difficult, in ways I would personally never act. Some of those moments—like with Asher in “Cheerful Until Next Time” or Lisa Parsons in “Ooh, the Suburbs”—are the moments I had to write and rewrite again and again until their behavior came to feel emotionally true.

Q: Animals make appearances throughout the stories. What draws you to include animals in your stories?

A: The original project of the collection, years ago, was to include an animal in every story. I had fostered 40 dogs during the course of four years in my twenties and I was really interested in how human neuroses changed the personalities and quirks of the dogs. I’ve always been interested in how animals play a role in contemporary life—how we imprint our struggles and desires on them, how they shape themselves around us.

Q: What is on your nightstand to read?

A: I’m currently reading We Do What We Do in the Dark by Michelle Hart—and zooming through it! I’m also so excited to read forthcoming story collections by Luke Dani Blue and Gothataone Moeng.

Q: With this collection published this summer and your new position in the fall, what are you planning next?

A: I’m currently at work on a novel called Songs of No Provenance, which tells the story of a folksinger wrestling with ideas around queerbaiting and the morality of artmaking. It also deals with themes of nonbinary identity and appropriation.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.