Jenn McKee, Pulp

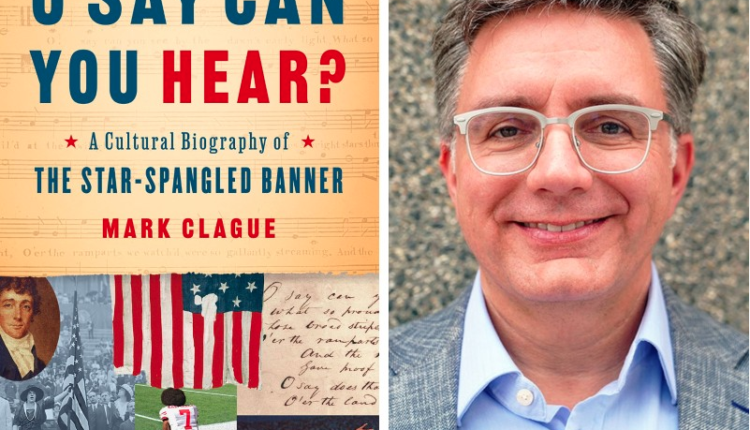

It seemed a little on the nose to be reading U-M associate professor Mark Clague’s new book, O Say Can You Hear? A Cultural Biography of the Star-Spangled Banner, on the 4th of July—at U-M’s Camp Michigania, no less—but that’s nonetheless when and where I absorbed enough national anthem-themed information to sweep an entire Jeopardy! category.

Indeed, to say Clague is thorough in his research would be a gross understatement.

In nine deep-diving chapters, the musicology and American culture prof covers: the circumstances surrounding the creation of Francis Scott Key’s lyrics; the man (John Stafford Smith) behind the anthem’s oft-recycled tune, known as “The Anacreontic Song”; past activists that regularly reworked the anthem’s words to promote their respective agendas (including temperance and abolition); the role of the anthem in war, particularly the Civil War; how the song came to have an enduring role in American sports; the way the anthem has been used in the context of protest; the controversy surrounding translations of “Banner” into other languages; the clash between the anthem and America’s history of slavery and racism; and why non-traditional performances of the anthem (think Jimi Hendrix, or José Feliciano, or Roseanne Barr) inspire a backlash—even as they sometimes point us toward a potentially fairer future.

There are loads of interesting, myth-busting tidbits in O Say Can You Hear? Many of us grow up hearing, for instance, that Key wrote the lyrics in a lightning-bolt burst of inspiration, with a single piece of paper, while imprisoned during the War of 1812; the truth, however, is that he wrote it over the course of three days, with access to plenty of paper, while stuck on an American vessel surrounded by the British. (Key was part of a pre-battle negotiation to get a captured colleague released.)

Plus, while we’re often told that the tune was originally a drinking song, Clague explains that Smith was commissioned to write the anthem as a member of an esteemed London music society that met, for a time, at a pub—but the establishment was more in the tradition of a high-end restaurant than a divey bar, and the primary focus of meetings was performance.

As these “Banner” tales get debunked, other interesting pockets of history come to light: like how, for many years, people would write lyrics about current events and set them to a handful of familiar tunes that most Americans knew—like “The Anacreontic Song,” for instance—and newspapers would regularly publish these musical “hot takes.” And it’s weirdly soothing to learn that while my generation faced the absurdity of politicians wanting to rename french fries “freedom fries,” in response to France’s criticism of the U.S. invasion of Iraq post-9/11, the World War I era’s anti-German bias led to this: “Rubella, or German measles, became liberty measles; hamburgers became liberty burgers.”

Changing “hamburgers” at least makes a kind of sense because they’re delicious and beloved. But measles already had a negative connotation. If this was about all things German being bad, wouldn’t you leave that one alone?

In any case, Clague digs in on specific, newsworthy past renditions of the anthem, dissecting artists’ choices and expounding on their impact. There’s even some “justice” for Roseanne Barr, whose seemingly tone-deaf pre-game performance inspired vitriol and hostility in 1990. According to Clague, her claim to have gotten derailed from delivering a “straight,” sincere version early on, by starting in too high of a register, appears to have merit.

More generally, I learned a ton from O Say but I’ll also say it’s not a page-turner. (Admittedly, for most of us, few history books are.) But O Say became way more fun for me when, in later chapters, Clague unpacked versions of the anthem—or even anthem-adjacent moments like Tommie Smith and John Carlos’ human rights protest at the 1968 Olympics—and I could go peek at these seminal “Banner” moments online. Armed with the knowledge of the song’s history and evolution, I had a deeper, more critically engaged experience.

Yes, an entire book could be devoted to the clash between the anthem and race in America—up to and including Key’s own status as an anti-abolition slave owner who also fought for many African-Americans’ freedom in courtrooms—but such contradictions and blind spots, Clague argues, are an important, integral part of the American story.

Clague writes:

Singing “The Star Spangled Banner” enables unity when content and expression harmonize with their social and political backdrop. When its performances instead elicit dissonance—for example, by calling for unity at a time when one group of Americans has been singled out as disadvantaged—our sense of being one national is instead disrupted, creating a crisis in patriotism. For democracy to function well, such community dissonance must be heard, recognized, and resolved. It is through this potential to make social dissonance audible and thus to demand change that “The Star Spangled Banner” exercises its social power. … Key’s lyric is less a call to sing than a call to compose.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.