by Martha Stuit

The 2,000+-mile Appalachian Trail spans the eastern United States from Georgia to Maine, traversing 14 states in total. The trail looms large in the consciousness of many people, from sightseers to thru-hikers. But how did such a major trail get created?

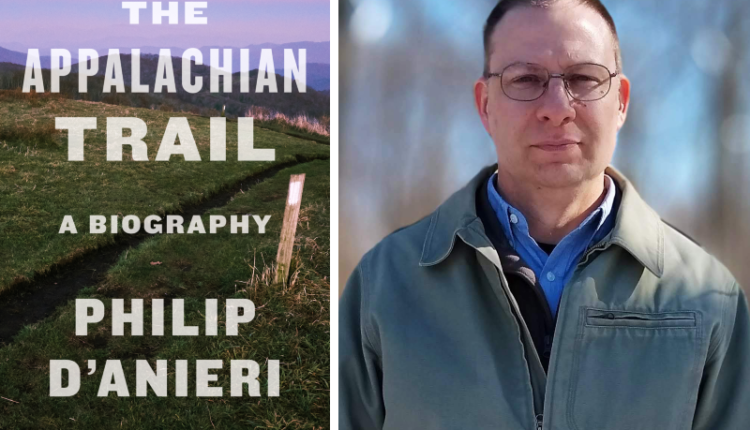

U-M lecturer Philip D’Anieri shows how the Appalachian Trail could not exist without the significant effort and devotion of instrumental individuals over time in his new book, The Appalachian Trail: A Biography. He provides not only facts about the contributors’ lives but also insights into who they were and what motivated them to contribute to the AT. D’Anieri also examines how the AT forms and fits into our views of nature.

Each chapter outlines how a different person (or people) helped shape the trail’s establishment. The trail’s development occurred alongside the growth of the United States, causing conflict when the trail was at odds with roads, politics, or interests of private landowners. The story begins with Arnold Guyot’s mapping of the Appalachian Mountains, as published in an article in 1861. In subsequent years, various individuals explore and build miles of trail, from the librarian Horace Kephart to Benton McKaye’s coining of the name “Appalachian Trail” in the early 1900s.

The first thru-hikers, Earl Shaffer and Emma Gatewood in 1949 and 1955, respectively, influenced the use of the AT. Another chapter depicts Senator Gaylord Nelson, who introduced legislation to federally protect the trail in the 1960s and also founded Earth Day in 1970. The book goes on to describe the challenges and successes of the National Park Service, which sought to obtain land along the AT’s corridor. Bill Bryson’s bestseller, A Walk in the Woods published in 1998, drew many to the trail, as D’Anieri writes in the penultimate chapter.

At the start and end of the book, D’Anieri reflects on the Appalachian Trail’s meaning in the public consciousness and his own engagement with the trail. In the introduction, he writes:

The places we choose, and the way we then develop and manage them, tell us a lot about what we are asking from nature, what exactly we think we are traveling toward and escaping from, where we want to strike the balance between maddening civilization on the one hand, and heartless nature on the other.

This question sets the stage for studying various individuals’ involvement in the AT’s construction.

D’Anieri finishes the book by discussing his adventures in driving the length of the trail and hiking short sections. His points that the Appalachian Trail is for everyone, and that there is much value to walking rather than driving, offer a current take on the trail. There is a great opportunity to interact with nature via the AT, to step away from our existing lives for a different outlook.

I interviewed D’Anieri to learn more about his book and the process of writing it.

Q: You grew up in the eastern United States. What were your first interactions with the Appalachian Trail?

A: As a kid riding in the car to see family in New England, I remember seeing the trail pass over the Massachusetts Turnpike on a pedestrian bridge, and I thought it was pretty cool that a trail got its own bridge over the interstate. Later, a close friend in high school, already a seasoned hiker, suggested that the two of us hike the AT of Maine one day. We never did, but the idea of the Appalachian Trail, this portal into nature that runs all the way from Maine to Georgia, has long been an intriguing place for me.

In doing research for the book, I hiked short stretches of the trail in each of the 14 states it passes through.

Q: How did you come to live and work in Ann Arbor?

A: I went to college at Michigan State and was working as a journalist in Detroit when I met my wife, who was starting law school at U of M. We moved to Ann Arbor and have been here ever since. Eventually, I went to grad school in urban and regional planning at the University of Michigan and have now been teaching at the university for 11 years.

Q: You teach courses on the built environment at the University of Michigan. What is the “built environment”? Does the AT fall into that category?

A: Traditionally the “built environment” meant places like city streets, college campuses, or neighborhoods—places where our surroundings are obviously built, separate and distinct from natural environments in more faraway places. But you don’t have to scratch the surface very deeply to see that that distinction doesn’t hold up for very long. Even a city street contains important parts of the natural environment like stormwater flows, and even naturalistic places like the AT are built in significant ways—the cleared trail, the overnight shelters, the parking lots that provide access. So what I was trying to do with this book was look at the trail through this lens of the built environment. How was it built? By whom? What were they after?

Q: The Appalachian Trail: A Biography covers many figures from history in each of its chapters. In regard to your own hiking of the trail, you write, “I treated the trail like one of the many archives I had investigated in researching this story. As when leafing through old letters or newspaper articles, I tried to observe the trail and its environment for the insights it had to offer.” Tell us about your efforts to research the trail. Where did you do research? What about the trail or people was most interesting or surprising to you as you researched?

A: Most of the original research was in library archives that hold the papers of the different people involved. The farthest north was in Augusta, Maine, and the farthest south in Cullowhee, North Carolina. One neat thing about the archival research is that it frequently put me near to the AT itself, and on many research trips I could get in a half day’s hike and experience a different part of the trail.

I think the most interesting part of the research was learning about these people as individuals—their personalities, their quirks, their motivations. Getting to know these folks on their own terms was fascinating in its own right, and then seeing how people so different from one another nevertheless found a kind of home for themselves in the idea of the Appalachian Trail was really intriguing.

Q: You also write about hiking, noting, “As I walked, a pleasant sense of separation from the world settled in, the subtly altered mental state that is in my mind the main reason to go for a hike.” It’s clear that you’re in good company with the creators of the trail who realized the value of hiking, too. Was that view part of what drew you to your research on the AT? Which of the AT’s key figures’ perspectives resonated with you the most?

A: What fascinates me about the trail, or really any place where we try to retreat into nature, is that it really does provide us with a window onto a world bigger than our day-to-day concerns, yet at the same time it exists in and is a product of that everyday world. The Appalachian Trail is the awe-inspiring vista from a mountaintop, sure, but it is also a piece of park infrastructure that has to be built and planned and managed like any other. The tension between those two aspects of the place is what defines it, in my mind, and that’s what I was trying to explore in the book.

I suppose it’s Benton MacKaye, who first proposed the AT in 1921 as a part of a much grander regional planning scheme, that resonated with me the most. He spent his whole life trying to find the right pattern for knitting together the built and natural worlds in a fair and responsible way. I don’t think he always got it right, but the questions he was asking were and remain important ones.

Q: Your last chapter, “On the Trail,” considers how the trail is for everyone, whether a thru-hiker outfitted with all the gear or a group of friends operating on soda and cigarettes. What do you hope people take from your book?

A: I really hope that people just enjoy it as a good read, like maybe a good New Yorker article, a window onto people and place that adds a little piece of new understanding about the world.

Part of that understanding in my mind is that the Appalachian Trail isn’t just one thing for just one type of user. The history of the trail, and especially of its protection by the National Park Service, makes clear that it’s a resource for people from all walks of life, going on lots of different kinds of hikes.

Q: You thank Jason Tallant and Jenny Kalejs of the University of Michigan Biological Station for the map illustrations. What did creating maps for this book involve?

A: The maps needed two things: a roughly accurate sense of where some of the places in the book were in relation to one another, and a visual presentation that was both clear and appealing. Jason took care of the first half, creating some bare-bones digital maps with just the right information on them, and Jenny then brought her considerable artistic skill to the task of sketching the maps in a visually rewarding way. I wish that some of them had gotten a more prominent layout in the book, to be honest, but that sort of thing is in the publisher’s hands.

Q: Any recommendations for further reading on the Appalachian Trail and/or hiking?

A: I’ve listed several recommendations on the book’s website, atbiography.com; if I had to recommend one, Robert Moor’s On Trails is excellent.

Q: What’s next for you?

A: Getting ready for fall classes! Teaching is what pays the bills, which is good because I genuinely enjoy it. Writing this first book was a tremendous learning experience, and I hope to put that to use in a forthcoming project, but I’m still noodling on what that might be.

Originally published in Pulp.

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.