ADL: Michigan Antisemitic Incidents Increase 21 Percent in 2020

by Todd Heywood, Michigan Advance

The normalization of antisemitism is continuing a “very, very troubling” upward trend in Michigan, despite a year of health restrictions and social distancing that often meant less human interaction.

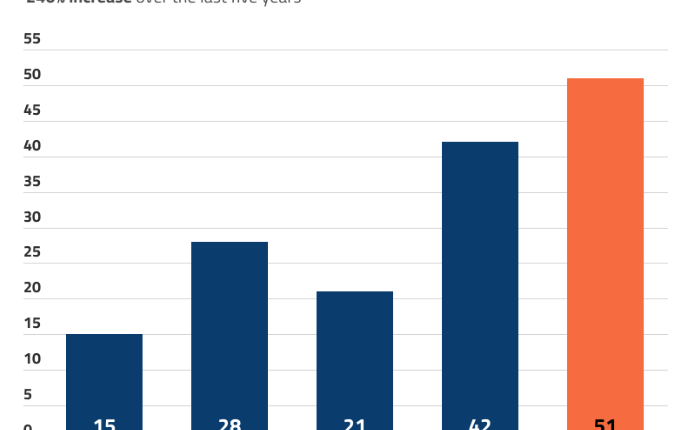

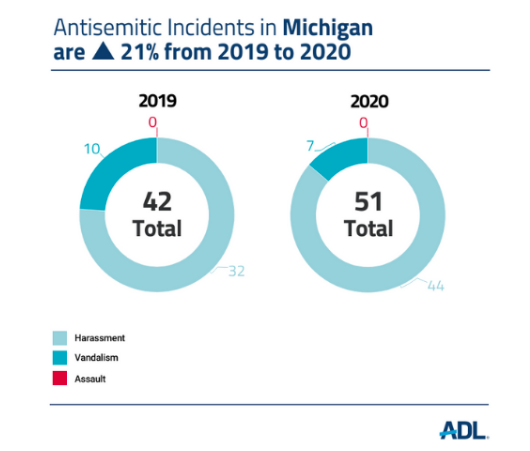

Since 2015, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) of Michigan has documented a 240% increase in reported antisemitic incidents in Michigan, starting with 15 in 2015 and increasing consistently each year to 51 incidents in 2020. It’s a 21% increase over the number of 2019 incidents.

Carolyn Normandin, ADL Michigan regional director, said the “ongoing upward trajectory” of antisemitic incidents is indicative of a troubling move to “normalize” the tropes underlying anti-Jewish sentiments in the state.

“One incident a week is a lot to deal with for a targeted community,” she said. “And it’s not just the person targeted, but any person in that group.”

Normandin said the organization only included those incidents which happened in Michigan and could be specifically documented. The organization also fielded calls about online purveyors of antisemitic products and ideas as well as antisemitic incidents occurring in other states. The reported numbers are an undercount, she said.

“We know there are more out there,” she said. “We know it anecdotally was well as from hate crimes statistics reported by the FBI and other law enforcement.”

Even as the state issued stay-home orders last year and mobility slowed because of the raging coronavirus pandemic, the ADL saw incidents of harassment increase — but in a new way.

As communities moved to online formats for meetings and education, such as Zoom, a new phenomenon arose: Zoombombing. That’s when an individual populates an online live meeting with a variety of examples of hate and harassment. Those could range from white nationalist symbolism to name-calling to someone flashing genitals during meetings.

“The pandemic didn’t stop hate; it merely reshaped it,” said Jonathan Greenblatt, CEO of the national ADL office.

This move, said Normandin, is problematic.

“Moving into this digital realm brings this hate right into your home,” she said. “Oftentimes, individuals are then left to process and address this alone. In other incidents, there is a group present to debrief with, to process it together.”

The pandemic also introduced a variable in antisemitic activity that the Michigan specific report doesn’t fully capture. During right-wing protests against coronavirus health restrictions, protesters were sighted with Nazi flags, images of Gov. Gretchen Whitmer with a small Hitler like mustache, and signs and speeches that Whitmer was “Whitler,” comparing her policies to those of the Nazis.

But Normandin noted that those political incidents, while certainly indicative of the normalization of antisemitic rhetoric in American politics, didn’t rise to the level of inclusion because the direct targets were not specifically Jewish.

“The COVID-19 rallies were an anomaly,” she said. In order to properly track emerging trends, she said, it is important to compare like incidents to like incidents.

Among those incidents that would be included were vandalism in which swastikas and references to Jewish peoples were displayed, verbal harassments including a Zoombombing incident in which a group of Jewish toddlers working on singing were assailed online, and physical assaults.

The one silver lining Normandin was able to point at in reference to the increasing incidence of antisemitic conflicts was that with the pandemic, there were no reports of physical assaults in Michigan in 2020.

Not all of the incidents documents by the ADL amounted to a criminal act or even a hate crime that could be prosecuted under state or federal laws. Attorney General Dana Nessel said in a statement that her Hate Crimes and Domestic Terrorism Unit was prepared to prosecute those incidents that did rise to the level of crime.

“There is no place for antisemitism in Michigan or this country,” she said.

The annual audit of antisemitic incidents in the United States has been conducted by the ADL since 1979, said Greenblatt. Last year had the third highest number of reported incidents in the history of the audit. That’s despite a 4% decrease in reported incidents nationwide, and a decline from the record high in 2019.

ADL also runs a running update of antisemitic incidents on its website.

The majority of online incidents involved persons with no documents history of antisemitic histories, said the organization’s Center on Extremism Director Oren Segal.

Nationally, the group also documented an increase in “scapegoating” the Jewish community for the coronavirus crisis. Online tropes included allegations that Jews created the virus, were actively transmitting the virus or were financially profiting from the virus and vaccines.

Normandin and Greenblatt both indicated the nation was at an inflection point in addressing antisemitism — and other hate.

“We’re not going to change the minds of the hardcore folks, the alt-right adherents,” she said. “But we can take action to address issues in our everyday lives. We have to speak out.”

And speaking out means understanding facts and being able to share them calmly and clearly, particularly within peer groups, ADL leaders said.

Normandin said it’s also essential that community members watch politicians — and not just on the state and national level.

“We need to know what the school board president and the members of the board of education are saying,” she said. “We need to know what county commissioners are saying. And we need to challenge it when it’s wrong. These are our leaders.”