by Rob Smith

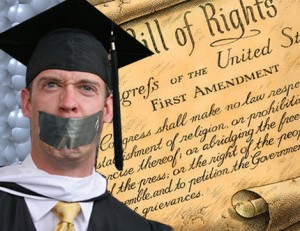

IN A REPORT released on Dec. 10, the Foundation for Individual Right in Education concluded that the University of Michigan and EMU are “red light” institutions when it comes to free speech on the campus. In fact, of the 12 Michigan colleges rates, eight were found to have policies in places that substantially restrict free speech for students and faculty. According to the report, “A red light institution is one that has at least one policy that both clearly and substantially restricts freedom of speech, or that bars public access to its speech-related policies by requiring a university login and password for access.”

In response, EMU spokesman Geoff Larcom said: “Eastern Michigan University seeks to be a welcoming campus, where many voices are heard and where robust debate about issues both external and internal is common.This is clear through visiting the many events on campus, including speakers on the day’s most challenging topics along with the participatory nature of our public meetings. Our student government leaders are actively involved in campus life, and have ready access to administrators and staff.”

The U.S. Supreme Court has called America’s colleges and universities “vital centers for the Nation’s intellectual life.” However, the reality today is that many of these institutions severely restrict free speech and open debate. Speech codes—policies prohibiting student and faculty speech that would, outside the bounds of campus, be protected by the First Amendment—have repeatedly been struck down by federal and state courts for decades. Yet they persist, even in the very jurisdictions where they have been ruled unconstitutional. The majority of American colleges and universities maintain speech codes.

FIRE surveyed 437 schools for this report and found that more than 55 percent maintain severely restrictive, “red light” speech codes—policies that clearly and substantially prohibit protected speech. Last year, that figure stood at 58.6 percent; this is the seventh year in a row that the percentage of schools maintaining such policies has declined.

The extent of colleges’ restrictions on free speech varies by state. In Missouri, for example, over 85 percent of schools surveyed received a red light rating. In contrast, two of the best states for free speech in higher education were Virginia and Indiana, where only 31 percent and 25 percent of schools surveyed, respectively, received a red light rating.

Virginia also took legislative action to protect students’ free speech rights in April 2014, when Governor Terry McAuliffe signed a bill into law effectively designating outdoor areas on the Commonwealth’s public college campuses as public forums. Under the law, Virginia’s public universities are prohibited from limiting student expression to tiny “free speech zones” or subjecting students’ expressive activities to unreasonable registration requirements.

Not all of the news is good, however. Although the overall trend is still towards fewer and less restrictive speech codes, this year a number of colleges and universities adopted more restrictive sexual harassment policies using language taken directly from the blueprint. FIRE continues to urge the Office for Civil Rights of the U.S. Department of Education to make clear, much like it did in 2003, that its regulations do not require universities to prohibit protected speech. Until OCR makes such a clarification in public documents and announcements, FIRE believes that more universities will adopt unnecessarily and impermissibly restrictive harassment policies.

Moreover, despite the dramatic drop in speech codes over the past seven years, FIRE continues to see an unacceptable number of universities punishing students and faculty members for constitutionally protected speech and expression.

What, then, can be done about the problem of censorship on campus? Public pressure is still perhaps the most powerful weapon against campus censorship. Students and faculty must be willing to stand up for their rights when those rights are threatened.

At public universities, which are bound by the First Amendment, litigation continues to be another highly successful way to eliminate speech codes. This year, FIRE launched its Stand Up For Speech Litigation Project, a national effort to eliminate unconstitutional speech codes through targeted First Amendment lawsuits.

FIRE’s hope is that by imposing a tangible cost for violating First Amendment rights, the project will reset the incentives that currently push colleges towards censoring student and faculty speech. Lawsuits will be filed against public colleges maintaining unconstitutional speech codes in each federal circuit. After each victory by ruling or settlement, FIRE will target another school in the same circuit—sending a message that unless public colleges obey the law, they will be sued.

FIRE surveyed publicly available policies at 333 four-year public institutions and at 104 of the nation’s largest and/or most prestigious private institutions. the group’s research focuses in particular on public universities because public universities are legally bound to protect students’ right to free speech.

FIRE rates colleges and universities as “red light,” “yellow light,” or “green light” institutions based on how much, if any, protected speech their written policies restrict.

Of the 437 schools reviewed by FIRE, 241 received a red light rating (55.2 percent), including the University of Michigan, 171 received a yellow light rating (39.1 percent), and 18 received a green light rating (4.1 percent). FIRE did not rate seven schools (1.6 percent).

U-M spokesman Rick Fitzgerald pointed to a statement in the school’s faculty handbook that says, “Free speech is at the heart of the academic mission.”

For the seventh year in a row, this represents a decline in the percentage of schools maintaining red light speech codes, down from 58.6 percent last year and 75 percent seven years ago. Additionally, the number of green light institutions has more than doubled from eight institutions seven years ago (2 percent) to 18 this year (3.6 percent). (See Figure 2.)

The percentage of public schools with a red light rating also fell for a seventh consecutive year. Seven years ago, 79 percent of public schools received a red light rating. This year, 54.1 percent of public schools did—a dramatic change.

FIRE rated 333 public colleges and universities. Of these, 54.1 percent received a red light rating, 41.4 percent received a yellow light rating, and 4.5 percent received a green light rating.

Since public colleges and universities are legally bound to protect their students’ First Amendment rights, any percentage above zero is unacceptable, according to the report.