The Foodist: The Dairy Industry is Starting to Lose its Stranglehold

A walk down the refrigerator aisle today looks a lot different than it would have 50 years ago.

by Lauren Rothman

REMEMBER THE DAYS when the standard accompaniment to a moist chocolate chip cookie was a cold, tall glass of milk? That ritual might soon be a thing of the past. Over the past few decades, milk consumption has plummeted, and an ever-diversifying set of plant-based dairy alternatives has hit supermarket shelves to take moo juice’s place in your breakfast bowl. “Got Coconut Milk Beverage?” sure doesn’t have the same ring to it as the dairy industry’s pervasive 1995 slogan, but if current trends continue, it might soon be a more accurate catchphrase.

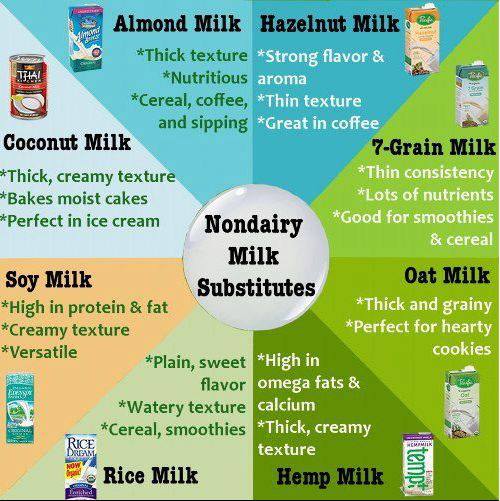

A walk down the refrigerator aisle today looks a lot different than it would have 50 years ago. Sure, cow’s milk still takes up a significant amount of real estate, but side-by-side with it are a variety of newer beverages, including the ubiquitous soy and the ever-more-popular almond milk. And the non-dairy choices don’t stop there: shelf-stable, carton-packed drinks such as rice, hemp, flax, oat and even quinoa milk can be found nearby. According to the market research firm Euromonitor, these dairy alternatives have averaged annual sales growth of 10.9% since 1999, and don’t show any signs of slowing down. Annual retail sales of the drinks currently average about $1 billion, a number that’s expected to rise to $1.7 billion by 2016.

The growth of the category makes sense when you consider how much less cow’s milk Americans are drinking: something has to fill the void. According to the U.S.D.A., consumption of milk has plummeted 25 percent since 1975. It’s a generational thing, the Department reports: Americans born in the 1990s drink milk less often than those born in the 70s, who in turn drink less than their parents’ generation. But since cookies and cereal are still around—and because consumers still want a convenient source of calcium and protein—soy, nut and grain milks are growing by leaps and bounds.

But why are Americans drinking less milk? Alisa Fleming, the author of Go Dairy Free: The Guide and Cookbook for Milk Allergies, Lactose Intolerance and Casein-Free Living, said that there are so many reasons for giving up milk that it’s hard to isolate just one.

“Dairy-free living has always been on the fringe—it touches on so many other issues,” she said.

A significant portion of the people who buy dairy alternatives does so because of taste: they simply don’t like cow’s milk, Fleming said, and they’ve wholeheartedly embraced the wave of substitutes.

“I see people who buy almond milk, and they’ve got cheese in their shopping cart right next to it,” she said. “So they’re clearly not eliminating dairy altogether. They’re buying almond milk because they prefer it.”

On the opposite end of the spectrum, Fleming said, is the growing number of Americans who are allergic to milk. Food allergies are on the rise overall, according to Food Allergy Research & Education, though researchers still haven’t come to a conclusion as to why. Milk allergies have always been common—along with eggs, nuts, soy, wheat and fish, milk accounts for 90 percent of all food allergies—but children used to outgrow the allergy by school age. Today, FARE reports, they typically don’t outgrow it until 16, if at all.

For those with an aversion to milk—especially those seeking relief from an allergy—the new wave of milk alternatives presents a tempting option. But in spite of their generally sunny, whole earth-type inspirational packaging and ad campaigns, these alternatives aren’t all benign. The environmental impact of farmed soybeans—a crop that is often planted at the expense of tropical rainforests previously rich in biodiversity—has been well documented, but the sad fact is that the rise in popularity of almond milk also poses a threat to the environment—albeit a much smaller one. All domestic almonds are grown in California, where in 2012 sales of the crop totaled $4 billion. The problem? The state is entering its third year of debilitating drought, and almonds are an extremely water-intensive plant. Indeed, the explosion of almond farming in the Golden State has reignited old arguments over water allocation there. The rice cultivation that produces rice milk, the second-most popular dairy alternative behind soy, is also a huge strain on the planet’s limited water supplies: rice production currently uses almost a third of earth’s fresh water.

For now, the limited popularity of beverages like hemp, flax and coconut milk has kept production of those crops within reasonable bounds. But as Alisa Fleming pointed out, once consumer advocates deem one particular crop unsustainable, the non-dairy milk companies find some other, less controversial type of plant to manufacture.

“The second someone says one milk is not sound, they jump into another crop and chop down rainforests to grow it,” she said.

It’s drink for thought.