URBAN EXILE: College Kids—The Hungriest of All Americans

By Christina Bravo

COLLEGE STUDENTS ARE terrible eaters. Those four years aren’t known as the time for juice cleanse experiments, after all. But perhaps we can’t blame their recent struggle with malnutrition on one too many bowls of mac and cheese. According to experts, there’s evidence that hunger on college campuses may now be much higher than the national average.

When Paul Vaughn, an economics major, was in his third year at George Mason University, he decided to save money by moving off campus. He figured that skipping the basic campus meal plan, which costs $1,575 for 10 meals a week each semester, and buying his own food would make life easier.

But he had trouble affording the $50 a week he had budgeted for food and ended up having to get two jobs to pay for it. “Almost as bad as the hunger itself is the stress that you’re going to be hungry,” said Vaughn, 22, now in his fifth year at GMU. “I spend more time thinking ‘How am I going to make some money so I can go eat?’ and I focus on that when I should be doing homework or studying for a test.”

Counting hungry students is hard because the issue is often shrouded in shame. On a Facebook page called GMU Confessions, an 18-year-old student with three part-time jobs confided anonymously last month that “I send my parents 50 dollars every month just so that they can manage to buy groceries, I have a 5 meal per week plan and I’m like REALLY REALLY hungry all the time.”

A problem known as “food insecurity” — a lack of nutritional food — is not typically associated with U.S. college students. But it is increasingly on the radar of administrators, who report seeing more hungry students, especially at schools that enroll a high percentage of youths who are from low-income families or are the first generation to attend college.

Though a nationwide survey has yet to be conducted, Western Oregon University has found that 59 percent of its students recently faced food insecurity. Other campus studies also show higher instances of hunger than the national rate of 14.5 percent. And this year Feeding America, which operates a nationwide network of food banks, will study the rising trend for its quadrennial survey.

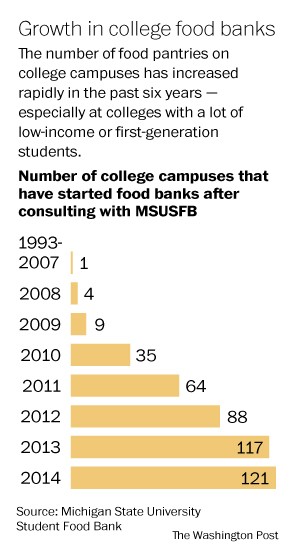

Thanks to the 2014 farm bill, unless they’re supporting a child under 12 or are working at least 20 hours a week, full-time students don’t qualify for food stamps. Universities have been coming up with their own solutions. Last fall Virginia’s George Mason University piloted a voucher program that gives away food coupons to disadvantaged students. Michigan State University students created the country’s first campus food bank in 1993. Since the Great Recession, other colleges have followed suit, and the number of university pantries has increased from four in 2008 to 121 today.

“Campuses across the country are starting to realize that there is that sector of people who don’t know where their next meal is coming from,” MSU Student Food Bank’s Nate Smith-Tyge told The Washington Post. “It’s not only a moral issue but also a curricular and academic issue.”

Even NCAA athlete and University of Connecticut student Shabazz Napier is affected by the trend; his basketball scholarship excludes expenses such as food. He recently told reporters that he sometimes goes to bed “starving.” “I don’t feel student-athletes should get hundreds of thousands of dollars, but like I said, there are hungry nights that I go to bed and I’m starving,” he told CNN.

A link between hunger and poor academic performance has been well documented in children but not in college-age students. Scientists have found, however, that hunger not only affects mood and behavior but also modifies pathways in the brain—which can only spell bad news for young people transitioning into adulthood.

Higher tuition and expenses have forced students to cut back on food, and an increasing number of youths from low-income families are enrolling—higher education has long been championed as the key to social mobility. But an empty stomach can only get you so far; we don’t need a study to prove that.