Urban Exile: Tiny Houses For The Homeless—An Affordable Solution

“THE TYPICAL development for extremely low-income housing is trending up toward $200,000 per unit. That’s a lot of bills,” says Jill Severn, a board member at Panza, a nonprofit organization that sponsors another tiny-house project called Quixote Village. (The organization’s name is a play on Sancho Panza, Don Quixote’s sidekick in Miguel de Cervantes’ classic novel.)

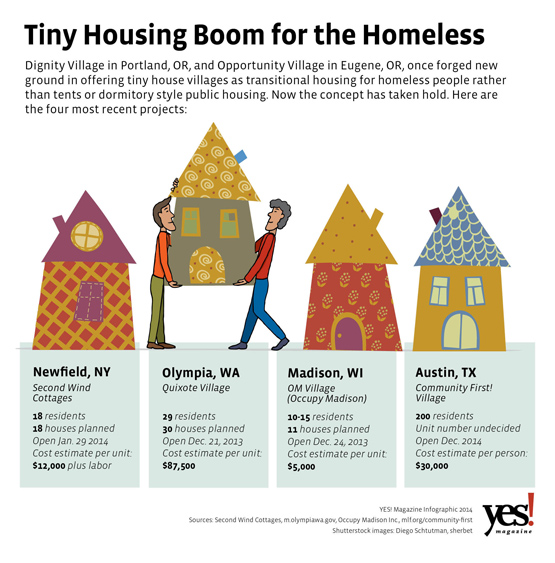

Quixote Village opened in Olympia, Washington right before Christmas. But it began in February 2007 as “Camp Quixote,” a protest held in a city-owned parking lot. A group of homeless people assembled there to oppose an Olympia ordinance that made it illegal to sit, lie down, or sell things within six feet of downtown buildings. When police evicted the campers eight days after the protest began, the Olympia Unitarian Universalist Congregation stepped in to help, offering temporary refuge on their land.

For five years, the camp’s location rotated, moving and reassembling every 90 days at one of several different local churches. Panza was formed by a corps of volunteers from the faith communities assisting the camp, and the organization worked with the city council to secure and rezone a parcel of county-owned industrial land near a community college and create a permanent site for the village. In December of 2013, the residents of Quixote Village settled into their new homes there.

Today, the 30 structures that make up Quixote Village are home to 29 disabled adults, almost all of whom qualify as “chronically homeless,” by the standards of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

The residents also have a common space with shared showers, a laundry, garden space, and a kitchen. By sharing these amenities, the community was able to increase the affordability of the project and design a neighborhood they believed would fit their needs and make them more self-sufficient.

The shared space has also helped them create a supportive community. The residents, who are self-governed, have developed a rule book that prohibits illegal drugs and alcohol on the grounds and requires that each member put in a certain number of service hours per week. They meet twice a week in the evenings to discuss problems or concerns and to share a common meal that they take turns cooking.

On a Saturday in September 2013, more than 125 volunteers showed up with tools in hand and built six new 16-by-20-foot houses for a group of formerly homeless men. It was the beginning of Second Wind Cottages, a tiny-house village for the chronically homeless in the town of Newfield, New York, outside of Ithaca.

On January 29, 2014 the village officially opened, and its first residents settled in. Each house had cost about $10,000 to build, a fraction of what it would have cost to house the men in a new apartment building.

The project is part of a national movement of tiny-house villages, an alternative approach to housing the homeless that’s beginning to catch the interest of national advocates and government housing officials alike.

For many years, it has been tough to find a way to house the homeless. More than 3.5 million people experience homelessness in the United States each year, according to the National Law Center on Homelessness and Poverty. Shortages of low-income housing continue to be a major challenge. For every 100 households of renters in the United States that earn “extremely low income” (30 percent of the median or less), there are only 30 affordable apartments available, according to a 2013 report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition.

But Second Wind is truly affordable, built by volunteers on seven acres of land donated by Carmen Guidi, the main coordinator of the project and a longtime friend of several of the men who now live there. The retail cost of the materials to build the first six houses was somewhere between $10,000 and $12,000 per house, says Guidi. But many of the building materials were donated, and all of the labor was done in a massive volunteer effort.

“We’ve raised nearly $100,000 in 100 days,” he says, and the number of volunteers has been “in the hundreds, maybe even thousands now.”

The village will ultimately include a common house, garden beds, a chicken coop, and 18 single-unit cottages.

“The typical development for extremely low-income housing is trending up toward $200,000 per unit. That’s a lot of bills,” says Jill Severn, a board member at Panza, a nonprofit organization that sponsors another tiny-house project called Quixote Village. (The organization’s name is a play on Sancho Panza, Don Quixote’s sidekick in Miguel de Cervantes’ classic novel.)

Many other tiny-house projects are just beginning to get of the ground, raise money, find land, and gain approval from local officials and members of the public. But the unorthodox nature of the small houses presents unique legal zoning limitations and barriers that limit where tiny houses can be stationed.

In Madison, Wisc., Occupy Madison has been facing this very challenge, as the group forged ahead with plans for a tiny house village.

In this case, the cost of building the tiny homes comes to around $5,000 each, funded by private donations and an online crowd-funding campaign. The nonprofit also plans to apply for some city grants. Each home will come with a propane heater, a composting toilet, and an 80-watt solar panel array—and will be about 98 square feet in size, 99 if you include the porch. (The volunteers enjoy the joke: “We are the 99 square feet!”)