by Lynn Parramore

CAN ART DO anything for the 99%? The case of Charles Dickens argues that yes—when genius, perseverance, activism, and admittedly, luck, combine, artistic creations can spark fires that burn through encrusted layers of human wrongs. It doesn’t happen overnight, and not as often as we wish. But it happens.

Maybe that’s why we’re turning to Dickens for guidance as America careens toward the nightmare he warned us about in the brutal early days of industrial capitalism. In this late finance-driven stage, as our top-heavy society teeters on the brink of self-inflicted disaster, we need him more than ever.

Dickens is a man for our season.

Poet of the People

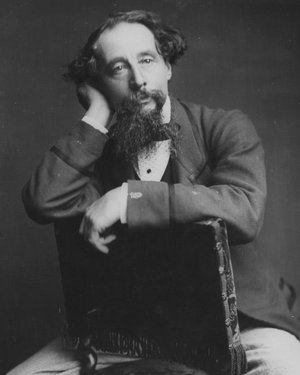

Dickens was the most famous writer in Europe and America during his lifetime, just 25 when his first novel, The Pickwick Papers, rocketed him to the heights of literary success. Ebeneezer Scrooge gave us the icon of miserly capitalism, while Oliver Twist indicted economic injustice in the simple request of a hungry child, “Please, sir, I want some more.”

A friend of the laborer, the poor, the prisoner, and the sufferer, Dickens was likewise the enemy of the miser, the hustler, the social climber, and the hypocrite, all of whom he could slice and dice in a fury of satire.

In the subjects Dickens took on we find a menu of concerns that reflect our current ills: laissez-faire capitalism (Hard Times), class divides (Great Expectations) child poverty (Oliver Twist), debt (Little Dorrit), legal injustice (Bleak House) and tyranny (A Tale of Two Cities).

No wonder Dickensia is everywhere right now. Since the financial crisis, there have been BBC adaptations, a hit biography, and retrospectives celebrating the 200-year anniversary of his birth in 2012.

Most recently, Bill de Blasio rode A Tale of Two Cities all the way to the New York mayorship, making the title of Dickens’ novel a campaign slogan for a divided metropolis. A new film version of “Great Expectations” featuring Helena Bonham Carter as Miss Havisham and an upcoming biopic starring Ralph Fiennes seal the author’s resurgence.

Charles Dickens didn’t just imagine hard times; he lived them. The world was very nearly deprived of one of its great artists and humanitarians when poverty struck his decidedly ordinary family. When Dickens was 12 years old, his father, a clerk, hit a rough financial patch and was thrown into debtor’s prison. Young

Charles left school and labored in a rat-infested shoe polish warehouse, toiling 10 hours a day, six days a week, for two years. If not for the death of his grandmother, who left the family a small inheritance, Dickens would likely have remained there and never continued his education. Fortunately he was able to make his way to school and eventually landed a job as a newspaper reporter.

Dickens’s childhood story, which haunted him for life, is a vivid example of what happens when people fall on hard times in the absence of a social safety net: they get trampled. No doubt Dickens and his family would have been sneered at today by Tea Partiers and self-serving 1 Percenters who pretend that poverty is a deserved condition. But Charles Dickens learned firsthand that poverty is no more a sign of depravity than wealth is an indicator of superiority. He saw that very often the reverse is true. This theme would feature in Great Expectations, where the working-class Pip longs to be a gentleman, but soon finds out that many gentlefolk were either dissipated or conniving or sadistic—or all three.

While Dickens wrote books, he also gave speeches, dispatched articles about social injustices and fought for changes to child labor laws, prison reform (notably, he abhorred America’s solitary confinement), and educational reform. Dickens wrote about the blight industrial capitalism created in Britain’s cities, while his contemporary Thomas Hardy wrote about the horrors brought to the rural landscape.

Dickens and Hardy, together with thinkers like Marx, Mill, Carlyle and Ruskin, laid the groundwork for 19th-century social reform. Part of Dickens’ genius was his gift for taking the messages of the intelligentsia and presenting them in a way ordinary people could understand and feel.

Dickens fell out of favor after his death: for several decades his realism seemed unfashionable and his moral earnestness antiquated. But in the aftermath of the Great Depression and the ensuing world economic crisis, his cultural stock shot back up. Dickens was heralded as one of the all-time great novelists in the 1940s by George Orwell and Edmund Wilson, and when David Lean’s adaptations of “Great Expectations” (1946) and “Oliver Twist” (1948) became cinema classics, his place as a cultural touchstone was secured.

Art and Progress

Dickens didn’t change things in the Victorian world overnight. Though his early books were popular, the public didn’t pay much attention to the social problems he criticized. It took time, prodigious output, a growing reputation, and tireless activism for his message to penetrate public inertia.

Today his books and stories fill class syllabi, and there’s a flash of media fascination, but does Dickens’ work really shape our consciousness? The answer is complex.

Dickens’ artistic mission is to present us with the possibility of radical transformation. There is no guarantee that the person leaving the theater or setting down the book will be moved to act differently.

Many a capitalist titan takes his family to see “A Christmas Carol” every year (or watches the Disney version on video) and then retires to his office to dream up new ways cut his workers’ retirement benefits. If conscience pricks him, he comforts himself with thoughts of his latest philanthropic ventures: “I’m not miserly, I just wrote a check to the ballet!”

Nobody wants to think of himself as a Scrooge. Billionaire bond titan Bill Gross recently had a Dickens-inspired moment when he admonished his fellow 1 percenters to pay their fair share in taxes and stop acting like “Scrooge McDucks.” “Having gotten rich at the expense of labor,” he mused, “the guilt sets in and I begin to feel sorry for the less well-off.” Is such reflection sincere, or merely exculpatory? Hard to say.

Clearly it’s not enough to rely on individuals having their humanity reawakened. It’s nice when it happens, but we need systemic, structural changes that will uphold fairness whether or not Scrooge gets religion. It’s not so much a New Me, but a New Deal that’s needed, a great shift in perspective that alters our cultural, political and economic standards. (Dickens was down with that — his more complex works point to the need for better systems as well as better people.)

But can art help get us there? Currently artists are flying in a headwind. The blockbuster paradigm set up by giant corporations sets ideological boundaries that are difficult to breach and choke out the possibility for nuanced and complex works of art that can easily reach mass audiences. The book industry is a mess, and it has become fashionable to look upon English and art majors as so many idle miscreants.

But some forms of art appear to be flourishing in spite of it all. We’ve seen documentary hits in the social change genre, like “Inside Job” (financial crisis), “Sicko” (healthcare industry), “Super-Size Me” (fast-food industry), and Detropia (urban decline), as well as small, break-out films like “Beasts of the Southern Wild” that focus on the lives of those capitalism has left behind. We’ve also seen a string of recent movies interrogating the institution of slavery in ways that may resonate, at least for some, with our current institutional ills, from “Lincoln” to “12 Years a Slave.”

Frank Rich complained in New York Magazine that productions like “12 Years a Slave” only serve to fill the liberal echo chamber, and it’s true that the Tea Partier is unlikely to be moved to see the racism in her creed—or even see the film. Such works of art are more likely to change us by their cumulative effect than generate instant transformation. But the cumulative effect can’t be dismissed: the positive portrayal of gays in popular culture in recent years may not have changed the mind of Billy Graham, but along with the activism it both inspired and reflected, this trend has helped shift the perspective of a generation.

The Dickens—or the Steinbeck—of our era of economic turmoil has not yet arrived, and perhaps, given fractured audiences and economic pressures, we shouldn’t hold our breath. But we do have powerful artists painting vivid pictures of suffering, poverty and abuse whose work is challenging the dominant cultural narratives and pushing back on the economic mythologies that have captured us.

We’re fortunate to be able to draw from the deep wells of artists like Dickens, whose insights are still clear and fresh two centuries after his birth. Please, sir, we want some more.